Nationalist narratives from WWII, resurrected during the 1990s War of Independence, continue to plague Croatian political life, with many potential consequences for the region.

On Tuesday, Croatia marked the 20th anniversary of Operation Storm (Operacija Oluja) by holding a military parade in Zagreb, memorializing the ‘liberation’ of the country and the ending of the War of Independence. While liberation parades have been quite popular this year during the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II, this parade has proven less popular than Croatia expected. Unsurprisingly, Serbia and Republika Srpska held counter-memorials in remembrance of the civilian victims of the war, while local Croatian NGOs also protested against the Oluja parade, arguing that there has been enough war and the time for reconciliation is now. But the parade went on, serving to memorialize the military actions of 1995 and to celebrate the nationalist narrative of liberation.

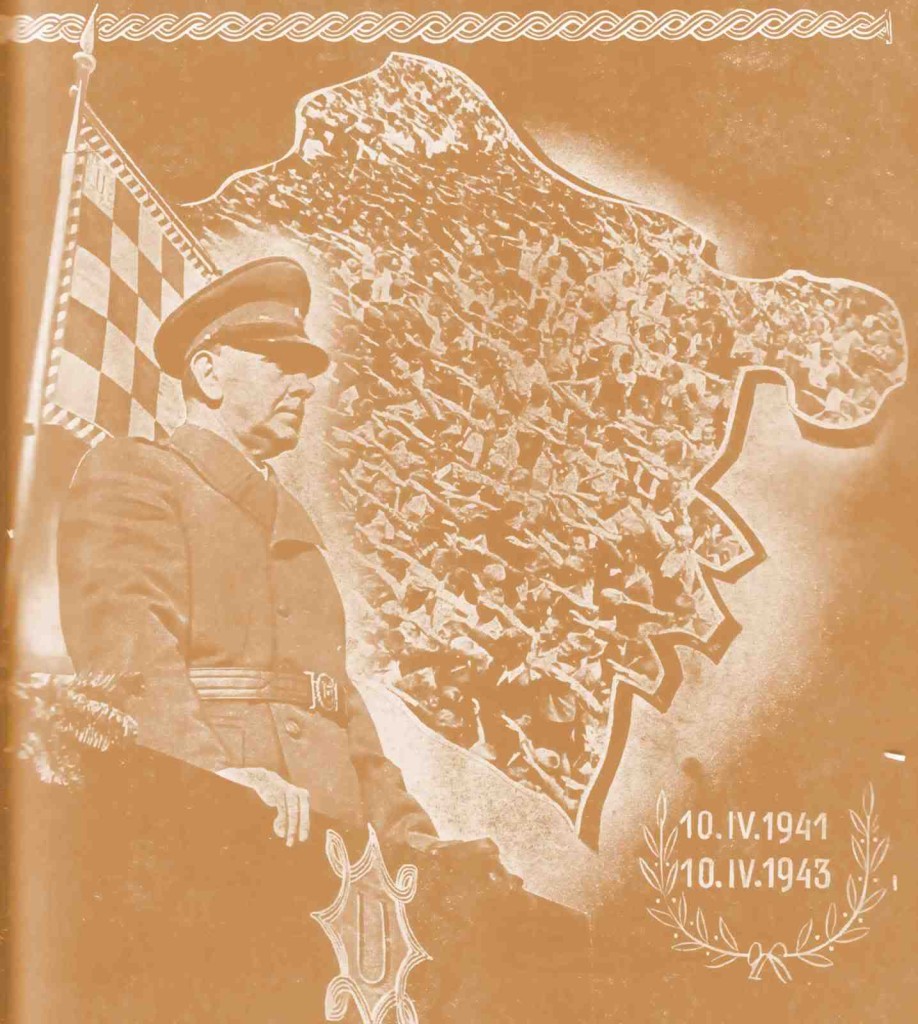

However, for some, the parade served as another example of the recent return to nationalist politics in Croatia. While the parade itself did not demonstrate an explicit outpouring of right wing politics, it did serve to remind many of the problematic narratives that surround Croatian independence and nationalist politics. However, the narratives of independence in the 1990s were built on the narratives of the previous independent Croatian state. Nationalists resurrected and utilized symbols of the 1940s Ustaše regime to cement Croatian nationalist narratives today, and those symbols have remained intertwined with national society. Through their resurrection in the 1990s and inclusion as part of Croatian national identity, the symbols have taken on a disputed character, serving to alienate many while promoting national pride among others. As the HDZ threatens to retake power in the Croatia parliament following the election of President Grabar-Kitarović, these narratives continue to plague Croatian political life. A national conversation about the symbols and the narrative legacies they created to obfuscate the complicated historical truths of World War II would only serve to directly benefit Croatia.

Symbolic politics and Narratives of Independence

The symbols of Croatian national identity today harken back to memories of the Ustaše regime during World War II. Deputized by Nazi Germany to control a large swath of territory, the independent Croatian state engaged in war crimes, the extent of which is still debated today, but which included complicity in the mass extermination of Jews, Serbs, and others throughout the territory. During the 1990s and the return of Croatian nationalism, Tuđman turned to the only symbols of an independent Croatian state in recent history to build national narratives and national identity throughout Croatia. Through the process of symbolic politics, Tuđman and others built nationalist myths of Croatian identity, venerating the symbols of the Ustaše regime and in the process denying the true atrocities committed by the regime during the 1940s.

While perhaps expected during the hypernationalist 1980s and 1990s, where myths of past glory flourished and certainly were not limited to Croatia, these nationalist narratives and symbols utilized in the war of independence have continued to exist and flourish throughout Croatia. This has been most clearly manifested through Croatian football culture, where the Croatian football federation has been penalized repeatedly for fascist-era chants and banners. But throughout the Croatian political space, the symbols and narratives are still very much alive, with HDZ candidates routinely denying Ustaše era crimes and regularly associating themselves with their symbols.

Of course, during the Ustaše regime, many Croats opposed the regime and even joined Tito’s resistance, and some supporters of the Ustaše regime turned against their policies when Ante Pavelić’s plans were made clear. Even Tuđman did not condone all actions of the Ustaše regime, but did claim it was an outpouring of Croatian desire for an independent state. Problematically, however, Tuđman and current HDZ politicians continue to refuse to apologize for crimes carried out by the Ustaše and work to augment the national narratives of the time to focus on the problematic Chetnik rebels rather than on the crimes of the Croatian state. This augmenting of the national narrative of the independent Croatian state serves to celebrate the continued strength of Croatia and the pride of the Croatian people, while downplaying the important history of the region necessary for reconciliation and the betterment of future relations.

Depressingly, augmenting history to support nationalist narratives is not unique to Croatia. Throughout the Balkans, the history of World War II is constantly being reinterpreted for nationalist reasons, often through the rehabilitation of war criminals, and the glorification of collaborators. Russia has been banning books and historians that discuss the country’s actions during their invasion and occupation of Germany in World War II. In Japan, the denial of war guilt and refusal to apologize for crimes committed during the war, has led to strained relations throughout East Asia. Even the United States has participated in the massaging of its history to promote national pride, with new high school history curriculums focusing on how America is exceptional, while downplaying aspects of its more difficult history.

Continually using nationalist symbols pushes nationalist narratives that at their core are exclusionary and divisive, encouraging actions that support only the national state and not reconciliation and regional cooperation. Even more troubling, however, is the lack of understanding of the role these symbols play and the meanings behind them. Symbols and narratives can take on new meanings over time, but their origins and their use over time remains important. Making sure an honest accounting of history accompanies the symbols is important. While some claim that nationalist symbols only serve to support pride in Croatian heritage, that same pride was created through violence against others.

A Path Towards Historical Reconciliation

The problem of historical symbols originally used in service of criminal violence and then reused to promote national pride is not a problem unique to Croatia. Most notably, the United States has recently had a much-needed discussion about the role of the Confederate Flag following the murder of nine African Americans at a prayer service in Charleston, South Carolina. Similar to some Croatian nationalists, supporters of the Confederate flag claim the flag does not represent slavery or other crimes committed against African Americans by their ancestors, but rather represents pride in the South and their ancestors’ bravery fighting during the American Civil War. They go even further, however, to argue that the war in the United States was not over slavery, but instead about States’ rights or other issues that promote a narrative more in accordance with their belief system. However, this narrative of bravery and the flag’s meaning accompany a 100-year tradition of historical revision, where the Dunning School and others changed the narrative surrounding the flag and confederate symbols, pushing the status quo to have southern states use the symbol regardless of how it made African Americans and others feel about the history. The symbols that stood for hate and violence became a source of pride for a subset of citizens, and many did not concern themselves with the pain it might cause elsewhere.

However, today the United States is having a national conversation and changing the narratives surrounding the flag and Confederate symbols, realizing how their portrayal is an augmentation of history. Similarly, Croatia will be well served by re-evaluating the history of their national symbols and coming to terms with the crimes of their predecessors. While Croats today are in no way responsible for the crimes of the Ustaše regime, politicians and nationalists continue to use and defend the symbols by changing the narratives of the past, which is no way forward. As the United States has shown with its example, the process of revisionism has only served to make national symbols cause pain for 150 years before they are changed and a conversation about the consequences of the past can finally take place.

The most important step Croatia can take now is for politicians to stand in opposition to the nationalist football culture, and to disassociate themselves from the fascist-era chants and symbols of the football pitch. As national identity seems to be recursively practiced throughout sports in Croatia, a firm stance against Ustaše symbols and chants must be taken. With the leading party in the country refusing to condemn chants that only serve to remind others of war crimes, the country commits itself to a nationalist path that ultimately does nothing to its benefit. While this will be difficult and the cohesive ideology of the HDZ is largely derived from these elements, it’s important to have this frank and important discussion.

Losing history and truth due to the privileging of narratives of revision that refuse to recognize the past will only allow the same mistakes and pain from the past to resurface. Support for national pride and narratives is not a reason to practice historical revisionism.