Last summer, while living in Odessa, I got in touch with British photographer Christopher Nunn, who has been working in Ukraine since early 2013. Nunn is not a conflict photographer or a photojournalist, and his photos are striking because they often look very different from other images coming out of Ukraine. We began a sporadic correspondence that later evolved into an interview. This conversation ultimately spanned many months and coincided with the evolving political chaos and war in the country.

Nunn spoke with Balkanist about everything from the media industry’s representations of the Ukrainian revolution and conflict, to embedding the confusion surrounding the war in his work, to the evident evolution of his own photography.

Can you explain the origins of your project in Kalush, the Ukrainian city at the foothills of the Carpathian mountains, which resulted in your published work, Kalush Part 1?

Well although I feel like I’ve talked about this part of the story too much I guess it’s important because it’s the context in which the work started. My grandmother was born in Kalush, and I went there to explore it and find out more about my history in a very loose, indirect sense. The Kalush publication was a small collection of my earliest photographs. It was well received but pretty naive, but that was ok because I knew it was just the start of something, and I did it partially to encourage me to carry on.

I had ideas about displacement, changing borders and language barriers in my mind as I wandered around. The work comes from a place of genuine intrigue and a desire to understand something about Ukraine and its people. That was the starting point that led to all these trips across Ukraine, which just so happened to coincide with political chaos, revolution and war.

I know much has changed in the last year to say the very least. Even in the seven months I spent in Odessa, far from the fighting in Donbas, I watched prevailing attitudes among people there change. Would you agree and how would you describe the changes you witnessed?

Yes I would agree. I saw changes in the way people were thinking and their understanding of what was happening in their country. My time was split between the east and west, often staying with regular working class Ukrainians, so I saw a lot of shifts in attitudes across the country during various points over the last year or so. A lot of people I knew seemed to change their opinion every other week. It was interesting to see a gradual acceptance or realization that Ukraine was changing forever, especially from people who thought the conflict would never reach them. It was the same for me as well. It was a time of growth and I was also trying to understand what was happening just like the people around me. It was always very confusing.

As someone who doesn’t focus exclusively on conflict photography, what do you think is missing from most of what we see in the western media? Has this made you think about differently about your own work?

Ukraine is missing in general from the western media most of the time these days. As with any conflict, the media industry reports what is ‘newsworthy’, and this is commodified and packaged for a mass audience. There is sometimes no wider context or understanding about these events or the country they are happening in. It’s important that it’s covered as much as possible in order to inform a global audience, but I also think it’s important to show another side. I can only really speak from a photography point of view, but the general media conforms to quite a specific framework that is based on decades of war reporting.

After a while I stopped paying attention to the media because I felt fatigued by the volume of information I was being inundated with, and decided to just try and focus on my own experiences in Ukraine. I went through phases where I felt pressure to respond to the conflict more directly, but over time it made less sense to me, and I began to question the conventions of conflict reporting, storytelling, media representation and this distance between what I was seeing on the news and what I was experiencing on the ground.

Donald Weber touched on something similar in a recent article, mentioning, as just one example, that the fire, ice and smoke of Euromaidan was only the surface of a much deeper situation, but this is the prevailing media image of what was happening, partially because it’s the most obvious and exciting thing to focus on, and the easiest thing to sell.

I felt like the more I tried to chase big events that could be considered ‘breaking news’, the more I missed a lot of other things that were very subtle but still in a way connected to the transformation taking place in Ukraine and its history. After all, I wasn’t there just because of the war, and my understanding, knowledge and connection to Ukraine goes back several years, and that was always a big part of the work.

You saw some of the very earliest fighting in eastern Ukraine, if I remember correctly.

I wouldn’t particularly say fighting as such, but rather some of the earlier events that were the start of the conflict in Donbas. I was in Donetsk, purely by chance, just as events in Kyiv were slowing down, and saw the east’s rejection of the Euromaidan movement in the form of protests, gatherings, and stormed government buildings. This was the so-called ‘Russian Spring’ and the beginning of Donetsk People’s Republic. A few months later I was back in Donetsk, when it had already fallen under the control of DNR and there was some fighting going on during this time as the conflict was escalating. I spent a few days with a Ukrainian army unit just outside Donbas who were preparing for battle and awaiting orders at the time.

Things were changing very rapidly, and all these events seem like a long, long time ago now. Most of the time though, when I wasn’t out photographing on my own, I was with regular local people doing ordinary, everyday things. I wasn’t driving around from one hotspot to another, or on the front lines, so what I did see was how they came to terms with, responded to, or ignored a rapidly changing Ukraine.

Are there any images of particular resonance to you, and why?

The images that resonate are often unexpected and come from some kind of genuine encounter or situation. My work relies on a degree of serendipity. They are often images that I didn’t really think about at the time, that I forgot about and only months later got round to looking at. I’m very slow at editing work. I’m drawn to quieter images, to the periphery, and while I’ve photographed soldiers on the front line, tanks, corpses, destroyed apartments and bomb shelters in the past it’s the things in between this that resonates with me.

I can only do what feels right for me and produce work as honestly as possible, and this is based on everything I’ve seen and done in Ukraine. I care about what I’m doing and the people I photograph, so hopefully other people will care too.

I remember you mentioning some months ago that you could hear incoming fire from a city which is the old capital of Slavo-Serbia. Having moved from Serbia to Ukraine last summer, I became interested in the history of the region and wrote about it for Balkanist, ‘Ukraine’s New Serbia and Slavo-Serbia: From Imperial Russia to Separatist Donetsk‘. I would be curious to know what that part of Ukraine is like right now.

I think what you are referring to is the time when Kramatorsk was shelled in February. Kramatorsk is the next city down the road from where I spent a lot of time. 20 minutes away by car. It was quite surprising when that happened, and it was during a volatile time in that region when things were escalating ahead of the ceasefire. I was also in Artemivsk when that got shelled which was also around the same time, so maybe you mean that.

I can only talk about my experiences of places I have stayed in for extended periods of time, in Ukrainian army controlled areas of Donbas (not including Donetsk which I visited up until May last year, when it was under DNR control). This isn’t necessarily on the front lines, but the threat, and presence of war is always there. It comes up in almost any conversation. There are soldiers in the streets, and tanks and APC’s driving along the highways to and from various points of the ATO. Travelling around can be slow because of military checkpoints that often have long queues. The roads are terrible and have been made worse by the heavy military vehicles. The streets are generally quieter, work is more scarce, shops can be low on goods, and in the smaller villages I stayed in there was often no running water for long periods of time (weeks or months), and regular power cuts. ATMs often don’t work and it can be very difficult to get cash, and there are problems with pensions. Train services are disputed and schedules are less frequent. The sound of artillery fire, both incoming and outgoing, is common and has at times been very frequent. It becomes part of every day life, and after a while it seems normal, but it’s the sound of war, and the sound of lives being destroyed in the distance.

Local people are very divided in what they believe. In Ukraine-controlled territory, where blue and yellow flags are everywhere, many people still support DNR and are against the Kyiv government, or even if they don’t actively support DNR or the idea of becoming part of Russia, they don’t trust the Ukrainian army. Others are very patriotic and fully support the government forces in the area. Some don’t care what happens either way as long as everything ‘goes back to normal’, and a lot of people simply don’t know what to think or believe anymore. Relationships often become strained or destroyed because friends or family members have conflicting views about who the ‘enemy’ is, and these views have become more extreme as time goes on. There is a lot of tension and distrust, and these are some of the invisible effects of war that influence my work. It’s under the surface, and it’s difficult to describe with a photograph, but it’s always there.

Away from the front lines, it’s the war around the dinner table, within the apartment block or in the workplace, or within the family; the ideological conflict and the cognitive dissonance of people living in a country in state of disorder, turmoil, and transformation. This is something that has informed my work more and more.

The information war, the use of propaganda is something that is startlingly obvious. There is a non-stop stream of stories, rumors, misinformation and blatant lies that sadly people seem to believe without question. This of course creates hatred and fuels the war.

Very few people I meet can speak English, which is something I’ve always embraced (I never expect anyone to speak English to me), and it’s become an integral part of my practice because I think the language barrier and this broken process of communication I constantly face in Ukraine somehow relates to my struggle with photography, or the limits of photography with regards to storytelling. It’s fragmentary and merely a suggestion of something, rather than being spelt out clearly, which is also one of its great strengths. My time in Ukraine was always confusing and that is something I want to show in my work.

There is a degree of paranoia in the streets, and at times it has been difficult to photograph freely because I am seen as a correspondent, which can raise suspicions. That’s understandable after the amount of propaganda these people have been bombarded with. I wanted to just disappear into these small towns and cities, wherever they may be in Ukraine, and just blend in and forget about the media coverage and the photography or art world, etc. Having said that, I’ve still met many people who haven’t really questioned me too much about who I am, and have welcomed me and invited me into their house. This is because I’m almost always on my own, which in itself has become more dangerous.

Aside from these things, life is very much like normal. People adapt and persist through difficult times. From looking at the news you would think that the entire eastern part of Ukraine had been reduced to rubble because of war.

One thing that’s always struck me when reading articles about Ukraine and looking at the kinds of photos that are published along with these texts is the way they portray Ukrainian and Russian people in ways they would never portray people from the US or the UK. I recall last summer some correspondents tweeting images of, say, dead naked men piled up in a refrigerator and commenting about the ‘stench’.

Our soldiers, who are always depicted as having dignity, would never be shown in such a light. In fact, I can’t remember the last time I saw a photo of an American soldier who’d been killed in Iraq, to say nothing of the description of the “stench” of their bodies. I think it’s interesting that we have one way of looking at/talking about our own brave soldiers, and another way of doing the same for soldiers and civilians in Ukraine. I was wondering if you’d noticed that or maybe had some general thoughts about it as a photographer in Donbas?

I don’t know. I’d suspect that it’s partially a question of access though; it’s easier to get access to the Ukrainian military than it is to get embedded with US soldiers, so there is less of a limit of what is ‘allowable’. I personally spent quite a lot of time in a hospital where horribly wounded soldiers were being brought from the front line, and no one really asked who I was or what I was doing. I saw things like the body of a soldier with his legs blown off and a separatist fighter who had been badly burnt, apparently in a tank, unconscious in the same room as wounded Ukrainian troops. Would I have had that access if they were American or British soldiers? I had all the necessary accreditation for working in the ATO, but that only goes so far. I’m not sure it would have been so easy in a situation with British or American soldiers, where there is no doubt more control over the press.

Also, because eastern Ukraine is a relatively easy conflict zone to travel to there have been so many photographers, particularly foreign, going there because they want to see action and excitement. They never cared about Ukraine until it became ‘exciting’, and it’s not that they believe their photographs can inform people and promote change, it’s about ego. This certainly isn’t specific to Ukraine, it’s happening all over. This isn’t strictly the fault of the photographers or journalists on the ground, it’s the whole media machine.

This absolutely does not apply to the vital and brave work that many great photojournalists, particularly Ukrainians, are doing, who care deeply about their country and want to show the world the horror of what is happening.

There’s one photo of your notebook from Ukraine with the hashtag #BREAKING#BREAKING#BREAKING written over and over again. What does it mean to you?

It was just some of my scribbles in a notebook. It wasn’t about anything in particular, probably just my frustrations with social media. It’s a hashtag that I find problematic and often used simply as click bait. I think when I wrote it I was just seeing #Breaking every time I looked at my phone, and thought a lot of it was ridiculous.

Then there’s your own hashtag, #Holywater, which you seem to pair with pictures of vodka and lakes. Did these images or experiences rhyme in some way?

Yes, it’s absolutely about things that rhyme. I’m looking for poetry, and connecting things that are not obviously related. I’ve said before that everything is connected somehow, and this seems especially true for Ukraine and its current position.

Themes of belief and faith are something that I’ve been thinking about for a while, and religion and vodka are both quite prominent within the domestic environments I’ve spent time in. I go through phases where I work towards specific themes so I could be looking for symbols and metaphors that relate to these themes. I was fascinated by ideas of belief or faith, and would photograph people physically holding on to things, kids jumping into polluted water wearing only boxer shorts and a crucifix necklace, people drinking, etc.

I won’t lie. I drink a lot in Ukraine, but I’m absolutely not saying that Ukraine is a country of alcoholics, because that is an old stereotype. It’s more about me being an English man, and so many of the people I meet have never met an English person before, and probably never thought they would, so they want to drink with me. So #Holywater was partially about that.

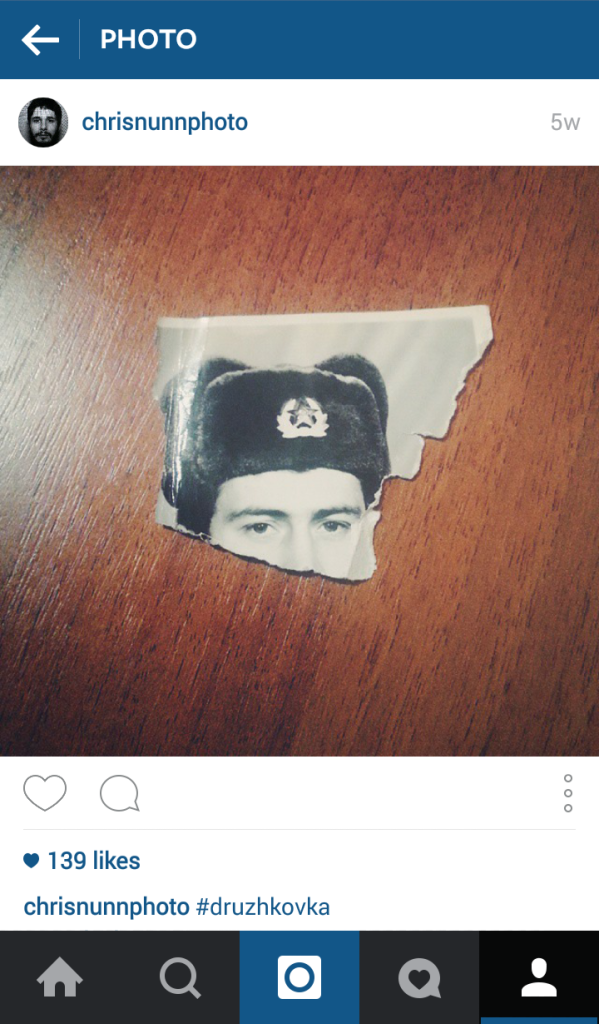

You like to photograph found photographs. I remember one particularly potent image of a torn photograph of a Soviet soldier’s face. While you do have some photographs of old Soviet monuments and a few rockets, unlike many photographers from the west, you don’t seem to fixate on these as symbols of some dead ideology. Your Soviet ‘subjects’ tend to be more found photographs of people who lived during that time.

I collect found photographs, letters, postcards, tickets, and all sorts of things from my travels. My aim is to use them within my work eventually. A friend gave the photo of the Soviet soldier to me. The man in the photo is her relative, and it was torn by accident. I immediately loved it because you can only see his eyes, so there is an obvious visual metaphor for to the current situation in Donbas, where we are used to seeing masked soldiers in random mismatched army fatigues.

As for the Soviet monuments, they have been heavily photographed, and yes they often look amazing, but it’s quite an obvious symbol of the dead ideology of Soviet times. For me the complex Soviet mentality that is all around is more fascinating, but almost impossible to describe with a photograph.

The monuments are just old relics that are part of the Donbas landscape. Local people probably don’t even think twice about them, and they are no different really to historical statues in our own towns that we would never think to photograph. The found photographs from Soviet times are more interesting to me, and I’ve been collecting things like this for years, even before I started my work in Ukraine.

I remember you saying somewhere that you hated photographing protests, political gatherings, anything of that kind. This seems linked to your attraction to the ‘peripheries’. What is it you don’t like about protest photography?

Well I enjoy being at protests and things like that, because they are usually interesting, as long as no one is getting hurt. I don’t actually hate photographing them, it’s more that the photographs are not really useful to me, and I always take the same pictures. I’ve never found a way to incorporate them into my work. They would probably work for a news feature or something but they are usually pretty boring for me, because it’s the opposite of what I’m actually looking for – protests are a display, or a show for an audience and they expect to be photographed, but what I’m looking for are quiet, subtle and unexpected moments and encounters.

All photos with permission by Christopher Nunn. Follow Chris on instagram @chrisnunnphoto, and visit his website to see more of his photography. Cover photo is from a pro-Russian protest in Donetsk, March 2014.