48 Photos

Life and Death in Five Former Secret Soviet Cities

Life and Death in Five Former Secret Soviet Cities

Source:The Soviet Union used to operate over 100 secret cities, stretching across Eurasia from Estonia to Kazakhstan. Their main purpose was to manufacture weapons of mass destruction. Today, at least 43 of them are still "closed cities" (ZATO), and they remain largely inaccessible to outsiders. But now it's possible to piece together their histories, and some of them may surprise you. There are cities filled with contemporary art we'll never see, and survivors of disasters we've never heard about.[separator type="thin"]

The morning after the Kremlin’s annexation of Crimea, in a Russian shipyard some 300 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle, a nuclear-powered cruise missile submarine called the Krasnodar burst into flames. The spent Soviet vessel still had two nuclear reactors on board while it burned, heaving heavy plumes of ink-black smoke into the atmosphere. Four kilometers away, the 12,000 residents of the ZATO (closed administrative-territorial formation) of Snezhnogorsk, a secret city in Soviet times, were just waking up. But when they looked out their windows that morning, they didn’t see a resurgent Russia, but an enormous black cloud.

Founded on a fjord in 1970, the former top secret Soviet city was built to house a workforce that could service nuclear-powered submarines. Today, the residents of Snezhnogorsk must work to disassemble and destroy some of the very same dangerously radioactive vessels. And though the population of about 12,000 has been slowly declining since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Snezhnogorsk and other closed cities still hide numerous secrets, and are home to some of the world’s most compelling sites you’ll probably never see.

Those who’ve been inside Russia’s secret cities describe a world both strangely beautiful and terrifying, filled with floating radioactive ghost ships, lo-fi noise artists, psychedelic murals, and some of the largest concentrations of nuclear reactors in the world.

As the burning Krasnodar submarine blackened the sky with smoke, a few brave onlookers took photos. They exchanged the images online, along with rumors about possible radiation exposure. But a spokesperson for the Nerpa naval yard later stated that the smoke emitted from the smouldering “Submarine 617” (as officials now refer to the retired Krasnodar) had been entirely safe to breathe. She assured the anxious population of Snezhnogorsk that the sooty clouds they saw spreading across the tundra of northwest Russia that morning in March contained not so much as a single particle of radioactive dust.

[caption id="attachment_4027" align="aligncenter" width="708"] The Krasnodar nuclear submarine in flames[/caption]

The Krasnodar nuclear submarine in flames[/caption]

At the height of the Cold War, an invisible and unmapped archipelago of over 100 secret cities covered the Soviet Union. They were modeled after atomic American cities like Los Alamos, New Mexico and Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and their purpose was the same: to facilitate nuclear research and the development of thermonuclear warheads. Most secret Soviet sites opened up by the mid-1990s, but the Kremlin acknowledges that about 43 ZATO still exist today. And experts in Russian nuclear security say they suspect an additional 15 cities continue to operate in near total secrecy.

Foreigners are generally prohibited entrance to all closed cities, though a select few have managed to obtain temporary, highly restrictive permits for certain towns following a lengthy, sometimes years-long bureaucratic process and the receipt of an invitation from someone on the other side of the razorwire fence.

Many people who live inside are endangered by the aging remnants of the Soviet nuclear program. Regional experts worry that isolating Russia too much right now could have some unforeseen and undesirable consequences. “The crisis in Ukraine will definitely make it much more difficult to get international funding to fix Russia’s nuclear problems,” Nils Bøhmer, a nuclear physicist and head of the Russian division for the Norwegian environmental organization Bellona, told Balkanist in a phone interview from Oslo. “And there is still so much that needs to be done.” Shortly after Russia was suspended from the G-8, the Russian Navy prevented a team of international scientists, including Russians, from testing radiation levels in an area of the Barents Sea suspected of contamination from a notorious and possibly leaking nuclear waste dump.

Dnipropetrovsk

[caption id="attachment_4072" align="aligncenter" width="4272"] Parus building in Dnipropetrovsk. Construction began in 1973 and has never finished. (Photo credit: Graham Phillips)[/caption]

Parus building in Dnipropetrovsk. Construction began in 1973 and has never finished. (Photo credit: Graham Phillips)[/caption]

“Envy killed the Soviet Union,” Russian historian Sergei N. Burin wrote.

Elite scientists in secret towns were granted special privileges to compensate for a life of isolation and invisibility. (Secret cities, once fenced in, disappeared from maps).

“Provincials, who lived in their own closed societies, envied Muscovites because Moscow was a real open city for them, and it had the better living conditions,” Burin explained. “Muscovites envied provincials, if they made successful careers.”

Shops in secret cities carried luxury food, and residents were often treated to more frequent time off from work. But inhabitants of most secret cities were also held to a higher standard of ideological purity than the rest of the population, and their freedom of movement was severely restricted. Many “provincials” came to resent Moscow for excluding them from the modern Soviet center. What finally doomed the empire, Burin believes, was when the “local intellectual elites”, often from closed, high-achieving scientific cities, “transformed their envy of Moscow into their new national politics”.

A new regionalism was born in the closed towns of Estonia and Ukraine, where a concentration of isolated experts began to create their own power structures independent from Moscow.

No city was more demonstrative of this kind of transformation than Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine. During the Cold War, the Russian-speaking city split by the Dnieper became one of the USSR’s chief strategic rocket and spacecraft production sites. The American media described the industrial town as a place that “harbored the Soviet Union’s deadliest secrets”.

Meanwhile, the region’s youth, workers, and powerful scientific and managerial elite had already been growing increasingly resentful of Moscow for decades. In 1968, more than 300 students and young intellectuals in Dnipropetrovsk signed the “Letter from Creative Youth” protesting the Russification of schools in the closed city. They were put on trial in 1970. Two years later, local workers protested against an influx of Russians into some of Dnipropetrovsk’s top secret factories.

For many years, post-independence Ukraine was largely controlled by what Moscow circles derisively call the “Dnipropetrovsk Mafia”. Former Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma served as the director of the Yuzhmash missile factory in Dnipropetrovsk -- the biggest in the USSR. Two Ukrainian Prime Ministers, Pavlo Lazarenko and Yulia Tymoshenko, were also culled from the same circles of power in Dnipropetrovsk.

But few are aware that the city’s future business leaders and famous politicians also sprang from the same throbbing disco circuit. Dr. Sergei I. Zhuk, a professor of Russian history released a book in 2011 called Rock and Roll in the Rocket City. The West, Identity and Ideology in Soviet Dniepropetrovsk, 1960-85. Zhuk, who also grew up in the Rocket City, says the clandestine introduction of rock, particularly Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple (a favorite of Dmitry Medvedev, as well as Serbian President Tomislav Nikolic), and especially dance music, helped foment rebellion against Moscow's authority, and inspired a reassertion of Ukrainian national identity. “Mary’s Boy Child (Oh My Lord)”, a Christmas cover recorded by the West German-engineered disco-Calypso group Boney M, also renewed interest in Orthodox Christianity and the scripture.

Shuk says former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko was a fixture on the secret Soviet city’s disco dance scene.

Lazarenko’s corrupt reign, first as governor of Dnipropetrovsk and later as prime minister, was characterized by an intensification of the rivalry between the Donetsk and Dnipropetrovsk administrative and business elites over control of resources like coal and gas.

This “rivalry” is clearly still very much alive today. Dnipropetrovsk’s new governor, Igor Kolomoisky, is an obscenely wealthy oligarch who’s spent over $10 million to arm and organize the Dnipro Battalion, a private corps of officers who occasionally enter separatist Donetsk, which is located just 150 miles away. Kolomoisky also owns Ukraine’s largest bank, PrivatBank, which famously promised $10,000 for the capture of pro-Russian separatists earlier this year. His new recruits are assigned to checkpoints around the former secret city where they stop cars that display Russian flags or other symbols, and search them for weapons. Most outlandishly, Kolomoisky recently offered to put up more than $135 million of his own money to build a 1,200-mile electric fence along Ukraine’s border with Russia.

"The objective is to prevent people from breaking in from a country waging aggression," he told reporters.

Dnipropetrovsk has been "open" since shortly after Gorbachev introduced glasnost, and while the city's leaders may no longer be the disco dissidents they once were, they never really stopped rebelling against Moscow.

Snezhnogorsk

[caption id="attachment_4076" align="aligncenter" width="453"] Снежногорска (Photo credit: vkontakte)[/caption]

Снежногорска (Photo credit: vkontakte)[/caption]

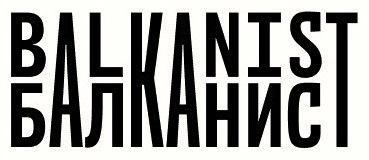

The apartment blocks in Snezhnogorsk are covered in vertiginous psychedelic murals. It seems likely that the anonymous artist was under the influence of some kind of mind-bending tundra mushroom while painting them. Residential towers in the Arctic ZATO are decorated in berries and bulbous onions, butterflies and faded rainbows.

Soviet officials founded Snezhnogorsk in 1970, and after that, it was known as Vyuzhny or by its radioactive isotope-sounding name, Murmansk-60. The city didn’t appear on maps again until 1994, but isolation from the outside world doesn’t appear to have turned Snezhnogorsk into a “Soviet time capsule”; it's actually pretty bold in its tastes when it comes to public art.

Recently, Snezhnogorsk held its spring fashion show. A group of seven teenage models with flat-ironed hair looked convincingly hungry and hollow-eyed as they wobbled down the catwalk. The eveningwear collection was good, and contained the most Russian references, with long gowns, rosettes, and red satin bodices. All of the designers and models were from one of the Kola Peninsula’s closed cities, meaning they were all from places built for the manufacture or maintenance of weapons of mass destruction.

And not far from the city center of Snezhnogorsk is the Nerpa shipyard -- the final resting place of the infamous Lepse. She doesn’t look like much more than a stately old cargo vessel, flecked with rust. But the Lepse is actually a “floating bomb”, filled with more radioactive substances than were released during the Chernobyl disaster. The 80-year-old vessel represents one of the single greatest dangers of radioactive contamination to Northern Europe. Scientists say the “radioactive ghost ship” is bursting at the seams with plutonium-239 and uranium-235 -- the two nuclear materials the Manhattan Project used to make the bombs that were dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

These days, the Lepse floats in the Nerpa shipyard, but scientists say it can’t take being in the water much longer. The Lepse is corroding, and desperately needs to be removed from the water and drydocked, so it can be destroyed by robots.

[caption id="attachment_4093" align="aligncenter" width="1082"] The Lepse being towed to the Nerpa shipyard in 2012. (Photo credit: Bellona)[/caption]

The Lepse being towed to the Nerpa shipyard in 2012. (Photo credit: Bellona)[/caption]

This process was supposed to begin in 2012, shortly after the ship was moved north from Murmansk, where it had been abandoned since the mid-1980s. For years, various organizations and governments had urged Russia to move the “floating Chernobyl” away from the 300,000 residents of Murmansk to the Nerpa shipyard, where its grim presence would threaten fewer human lives. But communication between the two institutions coordinating the Lepse’s transport, the Ministry of Defense and Rosatom -- the same two that clashed earlier this year over cutting off gas supplies to Ukraine -- broke down. As a result, the radioactive Lepse sailed right into a “submarine traffic jam” when it arrived at the Nerpa naval yard. The Leninsky Komsomol, the oldest nuclear-powered Soviet submarine, was already drydocked at what was supposed to be the Lepse’s parking place.

So the mesmerizing ghost ship has simply been bobbing in the Barents Sea ever since. Last year, the Russian government said it would be drydocked by the end of May 2014. But the crisis in Ukraine has slowed the decommissioning process down significantly, which means the Lepse’s lethal cargo of casks and caissons containing 639 spent nuclear fuel assemblies – equivalent to hundreds of tons of radioactive materials -- is still afloat in a bay in the Barents Sea, waiting to be destroyed.

Snezhinsk

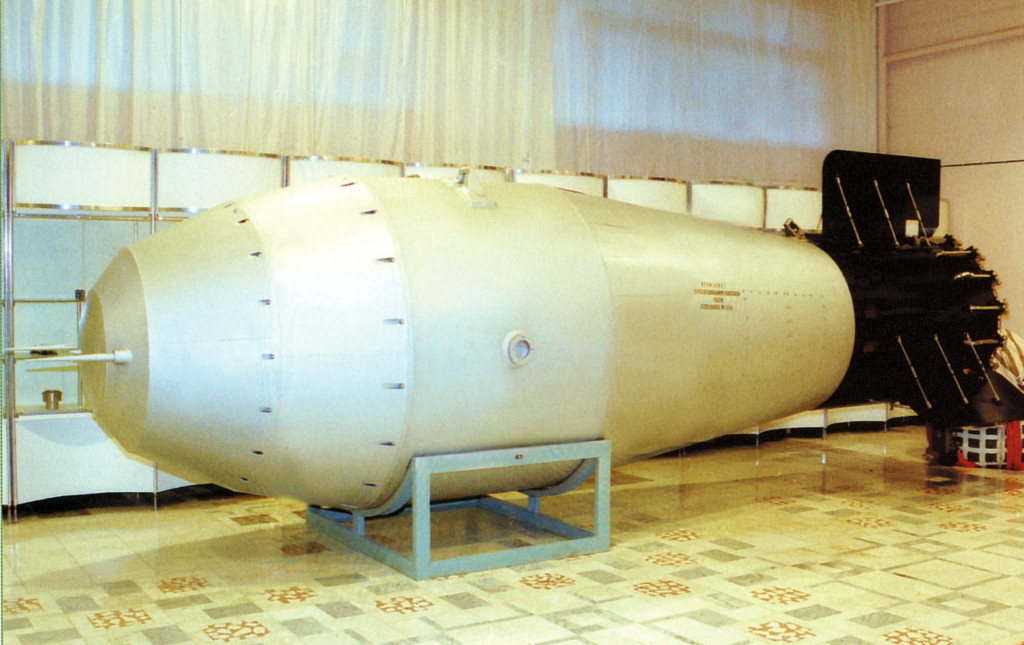

The world’s most impressive Museum of Nuclear Weapons must be in the closed city of Snezhinsk. Little pale pink missiles are on permanent display, alongside the “most powerful hydrogen bomb in the history of humankind”. Since Snezhinsk -- known as Chelyabinsk-70 until 1991 -- is a ZATO, few outside of the town’s 48,000 residents will ever get a chance to go on the guided audio tour.

Some of the brightest minds in the Soviet Union were sent to Snezhinsk, a city in the South Urals, to work at the All-Russian Scientific and Research Institute of Technical Physics. After 1991, when government funding for nuclear weapons research and manufacturing was cut, some of these same researchers and their children turned their attention to different fields.

Women’s liberation and the “philosophy of feminism” started attracting a certain segment of Snezhinsk’s scientists. While the Nuclear Research Institute had employed a significant number of women throughout the Soviet period, literature on activism and sexuality was pretty scarce. In 1995, a group of women formed an organization called Women from ZATO, and created an English-language website to communicate their objectives:

We are a young women's organization and there are only 20 members now. As most of us have technical education we decided that we need some kind of education in history and philosophy of feminism; in addition we were interested in the experience of Russian women's organizations and Women's Liberation in the USA and other foreign countries. This was the main reasoning for the creation in Snezhinsk of a Women's Information Center for women's and civil initiatives in our town and Chelyabinsk Region.

[caption id="attachment_4126" align="aligncenter" width="536"] Members of Women from ZATO[/caption]

Members of Women from ZATO[/caption]

Today, we are participants of the project "New Possibilities for Women" and we believe, we have enough resources to work as an Information Center: we have a computer, a printer, a copy-maker, a fax-modem, a hand tape recorder and a video recorder. We have a library where there are about one hundred books, journals, issues and documents, which we received from the Information Center of Independent Women's Forum and other sources. We have some video materials and video films, which we can use in our activity.

Women from ZATO later received some training from the Snezhinsk International Development Center Foundation (IDC), which launched in 2000. The IDC was a US government-funded program designed “to provide support and assistance for entrepreneurial activity and the nongovernmental organization sector in Snezhinsk during the course of integration into the market economy.” Most of IDC’s activities involved training professionals from different backgrounds in “financial planning and marketing”. The economy was in shambles, workers were going months without a paycheck, and unemployment was ruining families. The economic devastation that characterized 1990s Russia was felt even more severely in the secret cities, since they’d intentionally been hidden away in the most isolated parts of the country and were only designed to serve a single, highly specialized purpose, usually in the nuclear or aeronautical industries. The idea that trainings about entrepreneurship, innovation, and marketing did anything to improve the dismal situation seems doubtful. A decade after the IDC program’s implementation, Yury Rumyantsev, the deputy head of Snezhinsk’s administration, described the city as a “mono-economy”, and said that all the “engineers, physicists, and mathematicians find it extremely hard to get a job”. Rumyantsev also said that between 200 and 300 people were leaving town each year, often to go work on China or Iran’s nuclear program.

[caption id="attachment_4101" align="aligncenter" width="521"] Blear Moon[/caption]

Blear Moon[/caption]

In the absence of available work, some remaining residents of the closed city of Snezhinsk have apparently taken to making lo-fi ambient noise recordings. Blear Moon is a compulsively private man and a multi-instrumentalist who makes music that sounds like oblivion. A little research on Blear Moon reveals he’s likely Czech, so it’s possible that he’s not actually from Snezhinsk, but found the city muse-worthy. But more than one well-regarded music site has noted that his hometown is the ZATO of Snezhinsk. All the confusion does is add to the mystery. He certainly has been to the closed city, and done a good amount of photography and video art work there.

A few Blear Moon songs feature garbled vocal loops, including a passage from the 1908 English children’s book The Wind in the Willows:

“Seafarers we have ever been, and no wonder; as for me, the city of my birth is no more my home than any pleasant port between there and the London River… We [once] lay in wide land-locked harbors, we roamed through ancient and noble cities, until at last one morning, as the sun rose royally behind us, we rode into Venice down a path of gold…”http://vimeo.com/23021013

Severomorsk

[caption id="attachment_4103" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Disaster in Severomorsk, May 1984.[/caption]

Disaster in Severomorsk, May 1984.[/caption]

The nuclear submarine was docked 279 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle when Alexander Kuzmirykh went mad. The 19-year-old sailor from St. Petersburg spent his final days inside a 110-meter attack vessel that NATO referred to as akula, the Russian word for shark. When tragedy struck, akula wasn’t cutting through the Barents Sea, but docked in the secret military city of Severomorsk, the capital of the Northern Fleet. Kuzmirykh had been trying to alleviate the claustrophobic boredom of his post by getting high on glue and paint thinner for months. But there was no escaping the relentless darkness of the Arctic winter or himself. One night, the young sailor broke out of his sleeping quarters and murdered a guard with a chisel. Kuzmirykh armed himself with the dead man’s submachine gun, and shot another five crew members to death. Then he barricaded himself and two hostages inside the submarine’s torpedo compartment for 20 hours, threatening to set the nuclear-powered warship on fire and blow it up. Instead, he killed the two hostages and himself. Had the young sailor detonated the torpedoes while docked in Severomorsk, nuclear experts say it would have triggered something akin to a “second Chernobyl”.

Severomorsk is no stranger to tragedy. In 1984, two years before Chernobyl blew the lid off the Soviet Union’s disaster-prone nuclear program, a horrific accident occurred inside the secret city. Almost no one knows about it.

It began with a cigarette. A sailor took his last drag and threw the lit butt in no direction in particular. It was May 17, 1984, and the workday had just ended. That remaining bit of the sailor’s cigarette ended up igniting nearly half of the Northern Fleet’s ammunition. The main storage facility for the fleet’s ammo was in Severomorsk’s Okolnaya Bay. Almost half of the Northern Fleet’s stockpile was obliterated within 90 minutes. More tragically, between 200 and 300 people are believed to have been killed. The whole event is still shrouded in an air of pre-glasnost Soviet secrecy, so almost no one knows for sure exactly how many residents of Severomorsk died that day. But survivors have described a nightmarish scene: multiple missiles flying in wild corkscrew patterns, deafening simultaneous explosions, an enormous black, orange, and purple mushroom cloud, mothers running half-dressed with their children through the streets, the roads out of town jammed with cars. When news of the accident broke in the Western media months later, it was called “the greatest disaster to occur in the Soviet Navy since World War II”.

Right now, Russia is building a huge nuclear missile depot in Okolnaya Bay, the very same place where the ammunition disaster occurred exactly 30 years ago. It should be finished by October of this year.

Severomorsk is dominated by a hulking 27-meter high statue of a sailor. The blackened bronze “Seaman Alesha Memorial” is dedicated to the “heroes who defended the Polar region during the Great Patriotic War”. His intimidating figure looms over the city of 50,000, the main administrative base of the Northern Fleet. The ZATO of Severomorsk also has the largest drydock on the Kola Peninsula, and enormous nuclear-powered submarines lurk, half-submerged in water.Lise Bjorne Linnert, an artist based in Norway, had hoped to complete a simple project on the dock, near one of the submarines. Linnert has left stitched red thread in the public space of different cities as part of her “Fences” exhibition, and after applying for a special permit, she was given permission to do the same in Severomorsk. Elsewhere, she’d always been able to choose where she wanted to stitch what she calls a “trace”, but in Severomorsk she was instructed to use the entrance to the city park, where she “could view a statue of Lenin through the decorating chains given to stitch on.”

Still, Linnert says her experience of “stitching” in Severomorsk was unlike anywhere else because of the people. A local woman approached her while she was working and asked if she could help. The woman returned the next day and stitched beside her for eight hours. Of Severomorsk, Linnert said she'd experienced more openness in the closed city than she had anywhere else.

Fokino

The population of Fokino is disappearing. Since 2002, more than 3,100 people have left. Recent pictures seem to indicate that people left in a hurry, without any plan to return. Now there are whole apartment buildings that have been left vacant -- save for the trash and personal items people have left behind.

The ZATO of Fokino is located 45 kilometers south of Vladivostok, and is home to the Russian Navy’s aging Pacific Fleet. Several Sovremenny-class destroyers are waiting to be scrapped there, at least those that haven’t yet sunk into the depths of the the Sea of Japan. Something about Fokino is driving its longtime residents away in droves. Maybe it’s the same thing that’s causing others in town to have nervous breakdowns.

Exactly four years ago, 22-year-old Lieutenant Maksim Kuropatkin must have been having one of the most exciting days of his life. He was dressed handsomely in his crisp white sailor’s uniform, and looked like a happy young groom about ready to marry his pretty brunette bride in a strapless wedding gown with her hair up. Then the Russian president walked into the room. Dmitriy Medvedev was a “surprise guest of honor” during his tour of the Russian Far East. He handed the bride and groom big bouquets of pink and peach roses, and the three of them held overflowing glasses of champagne. “To a long happy family life,” then-President Medvedev said warmly. On his way out, he told a local official to make sure the couple got an apartment as soon as possible.

A few months later, the young couple got their new apartment. Kuropatkin, now a married man, had just graduated from the Pacific Naval Institute, and was on his first assignment, which happened to be Fokino. Just one month after the Kuropatkins moved into their new apartment, the young lieutenant shot himself in the head in front of two other servicemen. The preliminary conclusion was that “Kuropatkin suffered a nervous breakdown caused by difficulty adapting to life in the service.”

Fokino is apparently a very difficult place to live. In 2002, the Federal State Statistics Service of Russia recorded 26,457 inhabitants. Last year, they recorded just 23,306. Discarded furniture is tossed outside into mud puddles. Apartment blocks abandoned by their owners have been turned into makeshift garbage facilities. There has been little work on the Pacific Fleet, and people haven't been making much money in recent years. Then there's site of the submarine graveyard at the nuclear waste disposal plant.

[caption id="attachment_4109" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Putyatin Island (Photo credit: Airagency.ru)[/caption]

Putyatin Island (Photo credit: Airagency.ru)[/caption]

It's hard to believe, but Fokino is also home to a place many people call “paradise on earth”. The Island of Putyatin only opened to tourists recently. So far, visitors have been drawn to the island’s “unusual rose lotuses” that only grow in the Russian Far East, and the odd rock formation known as Pyat Paltsev (five fingers), because it looks like five fat fingers sticking out of the water. Rodnoe manor is also on Putyatin Island -- the former residence of Alexey Startsev, a wealthy merchant and the son of celebrated Decembrist writer Nicholas Bestuzhev, who used to pal around with Pushkin in exile.

Bestuzhev never saw the empty apartment buildings of Fokino, or the pretty little "eco tourism" island of Putyatin, but he finishes one of his most celebrated works, "A Frigate Hope", with the question: "But does there exist in this world even one thing, to say nothing of one word, one thought, one feeling in which evil has not been mixed with good?"

The Soviet Union used to operate over 100 secret cities, stretching across Eurasia from Estonia to Kazakhstan. Their main purpose was to manufacture weapons of mass destruction. Today, at least 43 of them are still “closed cities” (ZATO), and they remain largely inaccessible to outsiders. But now it’s possible to piece together their histories, and some of them may surprise you. There are cities filled with contemporary art we’ll never see, and survivors of disasters we’ve never heard about.

The morning after the Kremlin’s annexation of Crimea, in a Russian shipyard some 300 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle, a nuclear-powered cruise missile submarine called the Krasnodar burst into flames. The spent Soviet vessel still had two nuclear reactors on board while it burned, heaving heavy plumes of ink-black smoke into the atmosphere. Four kilometers away, the 12,000 residents of the ZATO (closed administrative-territorial formation) of Snezhnogorsk, a secret city in Soviet times, were just waking up. But when they looked out their windows that morning, they didn’t see a resurgent Russia, but an enormous black cloud.

Founded on a fjord in 1970, the former top secret Soviet city was built to house a workforce that could service nuclear-powered submarines. Today, the residents of Snezhnogorsk must work to disassemble and destroy some of the very same dangerously radioactive vessels. And though the population of about 12,000 has been slowly declining since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Snezhnogorsk and other closed cities still hide numerous secrets, and are home to some of the world’s most compelling sites you’ll probably never see.

Those who’ve been inside Russia’s secret cities describe a world both strangely beautiful and terrifying, filled with floating radioactive ghost ships, lo-fi noise artists, psychedelic murals, and some of the largest concentrations of nuclear reactors in the world.

As the burning Krasnodar submarine blackened the sky with smoke, a few brave onlookers took photos. They exchanged the images online, along with rumors about possible radiation exposure. But a spokesperson for the Nerpa naval yard later stated that the smoke emitted from the smouldering “Submarine 617” (as officials now refer to the retired Krasnodar) had been entirely safe to breathe. She assured the anxious population of Snezhnogorsk that the sooty clouds they saw spreading across the tundra of northwest Russia that morning in March contained not so much as a single particle of radioactive dust.

At the height of the Cold War, an invisible and unmapped archipelago of over 100 secret cities covered the Soviet Union. They were modeled after atomic American cities like Los Alamos, New Mexico and Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and their purpose was the same: to facilitate nuclear research and the development of thermonuclear warheads. Most secret Soviet sites opened up by the mid-1990s, but the Kremlin acknowledges that about 43 ZATO still exist today. And experts in Russian nuclear security say they suspect an additional 15 cities continue to operate in near total secrecy.

Foreigners are generally prohibited entrance to all closed cities, though a select few have managed to obtain temporary, highly restrictive permits for certain towns following a lengthy, sometimes years-long bureaucratic process and the receipt of an invitation from someone on the other side of the razorwire fence.

Many people who live inside are endangered by the aging remnants of the Soviet nuclear program. Regional experts worry that isolating Russia too much right now could have some unforeseen and undesirable consequences. “The crisis in Ukraine will definitely make it much more difficult to get international funding to fix Russia’s nuclear problems,” Nils Bøhmer, a nuclear physicist and head of the Russian division for the Norwegian environmental organization Bellona, told Balkanist in a phone interview from Oslo. “And there is still so much that needs to be done.” Shortly after Russia was suspended from the G-8, the Russian Navy prevented a team of international scientists, including Russians, from testing radiation levels in an area of the Barents Sea suspected of contamination from a notorious and possibly leaking nuclear waste dump.

Dnipropetrovsk

“Envy killed the Soviet Union,” Russian historian Sergei N. Burin wrote.

Elite scientists in secret towns were granted special privileges to compensate for a life of isolation and invisibility. (Secret cities, once fenced in, disappeared from maps).

“Provincials, who lived in their own closed societies, envied Muscovites because Moscow was a real open city for them, and it had the better living conditions,” Burin explained. “Muscovites envied provincials, if they made successful careers.”

Shops in secret cities carried luxury food, and residents were often treated to more frequent time off from work. But inhabitants of most secret cities were also held to a higher standard of ideological purity than the rest of the population, and their freedom of movement was severely restricted. Many “provincials” came to resent Moscow for excluding them from the modern Soviet center. What finally doomed the empire, Burin believes, was when the “local intellectual elites”, often from closed, high-achieving scientific cities, “transformed their envy of Moscow into their new national politics”.

A new regionalism was born in the closed towns of Estonia and Ukraine, where a concentration of isolated experts began to create their own power structures independent from Moscow.

No city was more demonstrative of this kind of transformation than Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine. During the Cold War, the Russian-speaking city split by the Dnieper became one of the USSR’s chief strategic rocket and spacecraft production sites. The American media described the industrial town as a place that “harbored the Soviet Union’s deadliest secrets”.

Meanwhile, the region’s youth, workers, and powerful scientific and managerial elite had already been growing increasingly resentful of Moscow for decades. In 1968, more than 300 students and young intellectuals in Dnipropetrovsk signed the “Letter from Creative Youth” protesting the Russification of schools in the closed city. They were put on trial in 1970. Two years later, local workers protested against an influx of Russians into some of Dnipropetrovsk’s top secret factories.

For many years, post-independence Ukraine was largely controlled by what Moscow circles derisively call the “Dnipropetrovsk Mafia”. Former Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma served as the director of the Yuzhmash missile factory in Dnipropetrovsk — the biggest in the USSR. Two Ukrainian Prime Ministers, Pavlo Lazarenko and Yulia Tymoshenko, were also culled from the same circles of power in Dnipropetrovsk.

But few are aware that the city’s future business leaders and famous politicians also sprang from the same throbbing disco circuit. Dr. Sergei I. Zhuk, a professor of Russian history released a book in 2011 called Rock and Roll in the Rocket City. The West, Identity and Ideology in Soviet Dniepropetrovsk, 1960-85. Zhuk, who also grew up in the Rocket City, says the clandestine introduction of rock, particularly Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple (a favorite of Dmitry Medvedev, as well as Serbian President Tomislav Nikolic), and especially dance music, helped foment rebellion against Moscow’s authority, and inspired a reassertion of Ukrainian national identity. “Mary’s Boy Child (Oh My Lord)”, a Christmas cover recorded by the West German-engineered disco-Calypso group Boney M, also renewed interest in Orthodox Christianity and the scripture.

Shuk says former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko was a fixture on the secret Soviet city’s disco dance scene.

Lazarenko’s corrupt reign, first as governor of Dnipropetrovsk and later as prime minister, was characterized by an intensification of the rivalry between the Donetsk and Dnipropetrovsk administrative and business elites over control of resources like coal and gas.

This “rivalry” is clearly still very much alive today. Dnipropetrovsk’s new governor, Igor Kolomoisky, is an obscenely wealthy oligarch who’s spent over $10 million to arm and organize the Dnipro Battalion, a private corps of officers who occasionally enter separatist Donetsk, which is located just 150 miles away. Kolomoisky also owns Ukraine’s largest bank, PrivatBank, which famously promised $10,000 for the capture of pro-Russian separatists earlier this year. His new recruits are assigned to checkpoints around the former secret city where they stop cars that display Russian flags or other symbols, and search them for weapons. Most outlandishly, Kolomoisky recently offered to put up more than $135 million of his own money to build a 1,200-mile electric fence along Ukraine’s border with Russia.

“The objective is to prevent people from breaking in from a country waging aggression,” he told reporters.

Dnipropetrovsk has been “open” since shortly after Gorbachev introduced glasnost, and while the city’s leaders may no longer be the disco dissidents they once were, they never really stopped rebelling against Moscow.