Describing himself as “a conservative nationalist first, a gay man second,” Melih Meşeli has little affection for Turkey’s other LGBTI groups and blames the protesters themselves for the crackdown.

Melih Meşeli looks shaken as he describes the last few weeks. As the founder of “AK LGBTI,” a paradoxical group of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) supporters of Turkey’s conservative, Islamic-based government, Meşeli has attracted a lot of media attention. But sitting in a café on a hill above Istanbul’s Golden Horn, he is worried about a recent spike in hate crimes and aggressive political rhetoric targeting the LGBTI population.

“The LGBTI question has become much more visible in recent years. The general public has started to notice the issue, so there has been a rise in homophobia. Homosexuality has always existed in Turkish society, but it was never in front of people’s eyes to the extent thta it is now, particularly in the media,” he says.

Meşeli is speaking weeks after the violent police crackdown on Istanbul’s LGBTI Pride March in Istanbul on June 28, which attracted international attention. The event has passed festively for 13 years but was banned at the last minute this year. Security forces blocked off the area surrounding the central Taksim Square and İstiklal Avenue, using tear gas, rubber bullets, and a water cannon to disperse tens of thousands of marchers. The authorities cited social sensitivity and the fact that the march was due to take place during the holy month of Ramadan, despite the fact that last year’s march also took place during Ramadan and passed without incident.

Describing himself as “a conservative nationalist first, a gay man second,” Meşeli has little affection for Turkey’s other LGBTI groups and blames the protesters themselves for the crackdown. Curiously for a purported gay rights group, AK LGBTI’s social media accounts largely stick to reposting pro-government memes slamming the ruling Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) critics.

“It’s not a crime to be LGBTI, but when the religious part of society has such sensitivity there is no need to push it on them. You can’t make them accept it in this way. You have to build the foundations first, you have to educate people,” Meşeli says. He shows me a video on his smartphone of three women dancing naked in the street on the day of the parade, as well as photos of marchers holding banners mocking religion. Both were shared widely by conservative critics to justify the police action.

Human Rights Watch condemned the ban on the march, while Amnesty International described it as a “new low.” The U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights said it was “deeply concerned by recent attacks, discriminatory treatment and incitement to violence in Turkey.” The Istanbul Governor’s Office, on the other hand, defended the crackdown, saying “no permission had been taken for the march, which was open to provocations.”

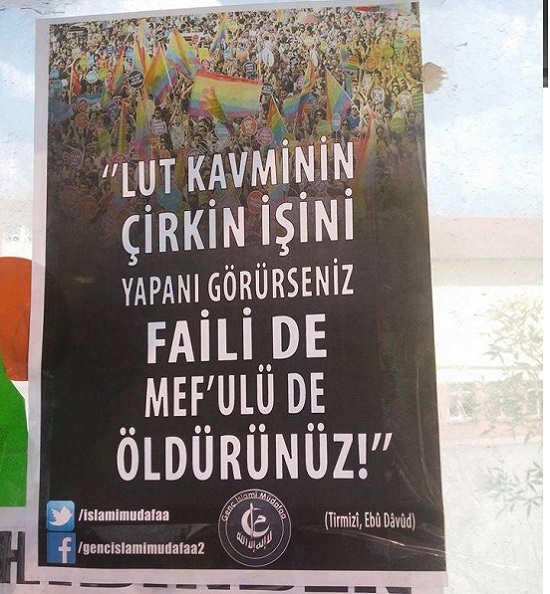

The police action came amid a notable uptick in incidents that have rattled Turkey’s LGBTI population. Throughout the capital of Ankara, a group calling itself “Young Islamic Defense” recently put up posters calling for the killing of homosexuals, quoting an interpretation of a hadith: “If you see someone engaged in the dirty business of the Tribe of Lot, kill them.” Also in Ankara, assailants broke into the home of the founder of an LGBTI sexual health association, Kemal Ördek, sexually assaulted him, and attempted to rob him, and yet were later released by police.

This comes after a general election campaign in which top government figures, including President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, labelled homosexuals as ‘enemies of the nation’ and described them as the “Tribe of Lot,” referring to the story of the sinful cities of Sodom and Gomorrah, which is widely known in Islamic tradition. Homosexuality is often derided in the AKP-aligned media as an artificial Western cultural imposition.

Yasemin Öz, a lawyer for the Ankara-based rights group KAOS GL, claims there is a direct link between the language used by Turkey’s politicians and public aggression against sexual minorities. “The police attacks on the Pride March take encouragement from the homophobic speeches of government politicians and the authorities,” she told me over the phone. KAOS GL has filed a criminal complaint at the public prosecutor’s office about the posters across Ankara.

A volunteer at news resource LGBTI News Turkey, who does not wish to be identified, agreed that political discourse fans the flames of violence. “The ‘Tribe of Lot’ language of Erdoğan, Davutoğlu and other high-level AKP representatives is reflected in the pro-government media. We think it leads to violence and hate crimes,” she said. The volunteer also drew attention to the contrast between the remarks of AKP figures abroad and at home. “Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arınç spoke at the U.N. in January and said LGBTs have equal rights, even if they don’t have specific protection. But after the police suppressed the Pride March he made completely contradictory statements in Turkey attacking LGBTs. It’s quite chilling to see two statements that are so completely different.”

In the June election, the opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) voiced support for LGBTI rights and the latter even nominated a gay candidate in one provincial town. Rights advocates praised the move but government figures seized upon it to slam the two parties and rally its conservative base, with President Erdoğan deriding the HDP as “terrorists, marginals, gays and atheists.” Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu also blasted the HDP, observing that “gays caused the destruction of the Tribe of Lot.”

There is a widespread sense that such rhetoric has risen in response to the increased public visibility of LGBTI activism. “Twenty years ago the movement in Turkey was very weak. There were only a few people struggling for LGBTI rights so it was easy to ignore them,” says the lawyer Öz. “But the LGBTI community is now much more powerful and is rising every day. I think fear of this motivates the conservative attacks against us. They understand that we’re now a power in civil society.”

Online news portal Bianet recently published an interview with İlker Çakmak, one of the organizers of the chaotic first attempted (but banned) Istanbul Pride March back in 1993. Çakmak painted a bleak picture of police violence, foreign supporters being deported, and suspected gays being arrested on the street. A march was not successfully held until 10 years later, when it was attended by just 40 people. But by 2014, around 90,000 people were taking part. For the 13 years of single-party AKP rule since 2002, the government was largely able to avoid discussing gays as a taboo topic – but no longer. The cat is now out of the bag, or perhaps the closet.

Yeşim Başaran, who works at LGBTI rights group Lambda Istanbul, agrees that a “conservative resistance” has arisen in response to the campaign for recognition. “The two things have happened at the same time. The issue of LGBTI rights has become more visible in the media and activists have become more vocal. Opposition parties have nominated gay candidates in elections and have LGBTI people working in their party organizations. That would not have happened a few years ago,” she says. “Life for LGBTIs in Turkey was never easy. They already were subject to attacks in public and within their families. They were at risk of being fired from their jobs or committing suicide. But in the last few weeks it has become more concrete.”

Legal complaints against the police crackdown and the Ankara posters are still waiting for a response at the prosecutor’s office. Meanwhile, Öz from KAOS GL says she is more worried than ever about the threat of physical attacks. “Perhaps for the first time in my life I think we have to be more careful than before, because they recognize that we’re more powerful. But I’m not frightened about going out. If something happens, there’s nothing you can do to stop it if they want to harm you.”

For those crossing multiple boundaries, like the members of AK LGBTI, the situation may be even more dangerous. Its founder Meşeli compares the group to “Fenerbahçe supporters at a Galatasaray match.” Many people have assumed its social media pages are troll accounts, but Meşeli is clearly very earnest. He says they want to gain legal “association” status to help like-minded people who he claims are “under-represented” by other LGBTI groups. But the recent rise in tensions has pressed them to keep a lower profile for the time being. Meşeli previously gave a series of interviews in the Turkish national press, but now he thinks twice before agreeing to meet reporters. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he says his group’s attempts to reach out to the AKP itself have had little success.

Now, with a fresh election looking increasingly likely after the inconclusive June 7 vote, the AKP may again resort to homophobic rhetoric to woo wavering conservative supporters. The situation for LGBTIs in Turkey has advanced rapidly over the past decade, but the clouds once again seem to be darkening. Whatever happens, the issue looks set to continue to expose Turkey’s delicate cultural and political fault lines.