The presidential election in Romania will be held in an atmosphere dominated by a series of spy and corruption scandals. Enter Mr. Klaus Iohannis, the “refined” German-Saxon mayor of Sibui, who some say is a refreshingly different kind of candidate in Romania. He will be competing against Mr. Victor Ponta, the current prime minister whose campaign rallies have been referred to as “Ceaușescu redux”

In June 2000, a retired high school physics teacher named Klaus Iohannis was elected mayor of Sibiu, a city of 150,000 tucked into the Carpathian Mountains of central Romania. His goal, he declared in a series of local rallies, was to revitalize Sibiu, once “Hermannstadt,” an Austro-Hungarian city studded on the Ottoman frontier. Misrule by Romania’s fascists, Stalinists, nationalists and post-Revolutionaries had crippled Sibiu’s economy and cast the former Habsburg capital into a cultural abyss.

“Sibiu was forgotten by the Communists and the neo-Communists. There were water pipes still left over from 1910,” Iohannis writes in his newly-issued autobiography “Pas Cu Pas” (“Step by Step”), currently on display in book shops across Romania. Within two years, the incumbent mayor was streaming new economic blood into Sibiu. In the city’s western quarter, once one of the most polluted agro-industrial plants of Communist Transylvania, he revamped rusted-out factories into tech centers. Cheap Romanian labor triggered a barrage of foreign investment – banks, software companies, financial firms – and raked in unprecedented tax revenue. Between 2002 and 2003, Sibiu’s city budget leaped 61 percent. Unemployment rates plummeted to 0.8 percent, among the lowest rates in Romania and Europe at large. “I think Iohannis was successful because he didn’t approach Sibiu as a public official would,” says Flavio, 34, a medical student in Cluj-Napoca. “Instead, he approached it systematically, like a businessman.”

Next, Iohannis set out to make Sibiu the greatest tourist attraction between Budapest and the Black Sea. A tourist board was established and the dismal Sibiu airport refurbished into an international hub. The city’s hotel capacity quadrupled. “Young Since 1191” ran the city’s new slogan, emblazoned on shiny, free new guidebooks. Over time, a certain brand of tourist started choosing Sibiu over medieval cities in Central and Western Europe. Sibiu was cheaper, less Disneyfied. By 2005, 40 percent more were coming each year.

In 2007, the same year Romania joined the European Union, Sibiu was declared its cultural capital. The city’s stunning rebirth made Iohannis the only city mayor that average Romanians could identify on a national level. Most Romanian politicians specialize in inefficiency, but Iohannis was known for getting things done. (“Less Talk, More Things Done” is a campaign creed.) He was equally revered for what he didn’t do, refraining from rowdy parliamentary theatrics – other specialties of Romania’s elected officials. He cultivated a favorable relationship with local newspapers and endeared himself to Western leaders during frequent trips to Germany and Austria. He was re-elected by suspiciously wide margins and owned a fleet of fancy homes, but his corruption was hardly extreme by Bucharest standards. “Public administration in Romania is utter chaos,” says Elena, a computer science professor in Sibiu. “Don’t get me wrong. Iohannis is no more honest than our other politicians. But he is somehow more refined.”

That’s the consensus across Romania: Iohannis may be a politician, but not of the sort Romanians are used to seeing on their ballots. He is currently one of two leading candidates for the Romanian presidency, to be decided onNovember 16. “If it is possible in Sibiu, it is possible in the whole of Romania,” Iohannis has insisted on campaign platforms for the last two months. His national popularity is astounding – one in three Romanians now stand with him – and unexpected; ethnically, Iohannis is not Romanian but German. His ancestors were among the Saxon settlers who migrated to Transylvania in the 12th century. Iohannis himself was among the few not sold back to Bonn by Nicolae Ceausescu between 1978 and 1989. The German connection jumpstarted the mayor’s success – it was primarily German companies that he succeeded in luring to Sibiu – and motored his drive to national prominence. When you ask Romanians about Iohannis, some will draw a line back to Romania’s ethnically-German royal family, still well-regarded in certain circles. Others will cite prevalent if tired clichés about German work ethic. But most Romanians, disgusted with endemic public corruption, are just relieved that Klaus Iohannis isn’t Romanian.

The other contender: Victor Ponta

Victor Ponta, 42, was once an inspiring Romanian political figure, appointed Europe’s youngest prime minister in 2012. Scandal after scandal has since soured those impressions. The prime minister was never able to adequately dismiss accusations that he had plagiarized his doctoral thesis. The PSD, his center-left Social Democratic Party, fell under a wave of international outcry for appointing known anti-Semites to key cabinet positions. More recently, Ponta had a nasty, highly-publicized falling out with Traian Basescu, the current Romania president who, despite running on an anti-corruption platform, has finished his second term in a quagmire of corruption. To secure Basescu’s impeachment, Ponta drummed up his own war against the rule of law – threatening judges, illegally removing top officials from government posts and tampering with Romania’s constitution.

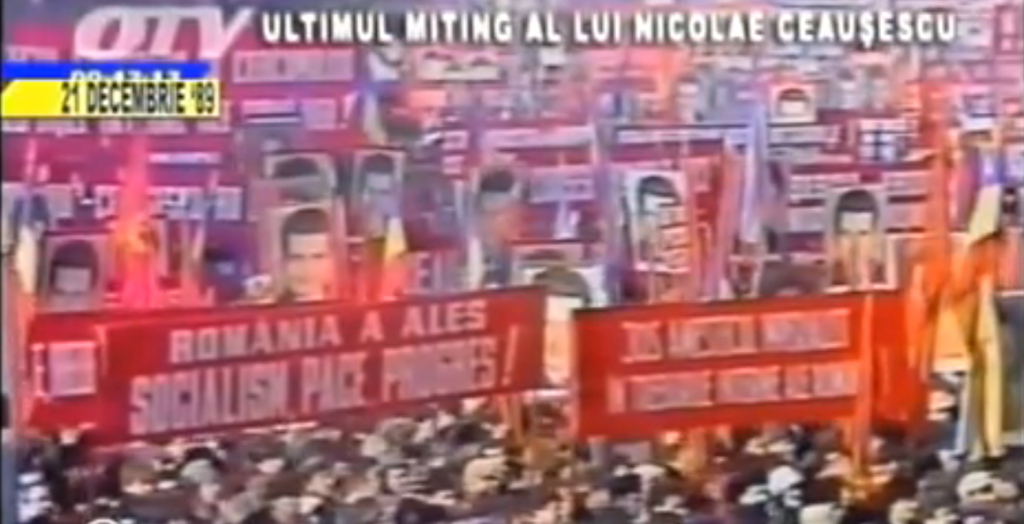

On September 20, Ponta celebrated his birthday by launching his own bid for the Romanian presidency. He summoned 70,000 of his countrymen to a two-million euro extravaganza at Bucharest’s National Arena, which he had decked out in enormous Romanian flags, folksy cutouts of medieval Wallachian warlords and red “PROUD TO BE ROMANIANS” banners. “I call on you all to embark together on the path of change,” Ponta proclaimed, “to stand together on the road to Grand Unification of all Romanians.” This poorly-veiled re-invigoration of Ceausescu’s vast popular rallies was not lost on political pundits – “Actually, Ceausescu held his party congress at the Sala Palatului,” Ponta objected – nor by spectators across Romania.

For many Romanians, the Ceausescu redux is not necessarily a bad thing. The dictator’s legacy remains almost unassailable in large swathes of Moldavia and Wallachia. Unlike Transylvania, these provinces are some of the poorest districts in all of Europe; historically, they comprise “Old Romania” and have been electoral bastions for the PSD, a direct outgrowth of the Romanian Communist Party, since 2001. The mood in Eastern Romania is markedly different than that in the West. “All that corruption you see across Romania today? Nonexistent under Ceausescu,” a middle-aged man informed me in Dobrogea. “Romanians had significant privileges under him. Under the EU, we feel like an embarrassment.”

To make up for centuries of Romanian backwardness, the country’s Communists attacked its prosperous minorities: Hungarians, Jews and Germans. This remains a favorite tactic of campaigning politicians, despite the virtual abolishment of all those groups. Also in the running for the country’s presidency is a man named Corneliu Vadim Tudor – a fervent expansionist who insists that the Holocaust never happened in Romania. Another candidate is Gheorge Funar, a former mayor of Cluj-Napoca who once gilded the city’s benches in Romanian colors in a bid to prevent Hungarian minorities from sitting on them.

Ponta, meanwhile, has re-deployed the Ceausescu legacy in another direction, doctoring a close association between himself and the state. “We will send people to Brussels who are proud of being Romanians – who will defend Romania,” the PSD promised before May’s European elections. For the past two months, Ponta and his wife have toured Romania pledging to uphold “the army, church and family.” Ponta can tout himself as a defender of Romania because he is “Romania”: an avowedly Orthodox family-man.

The implicit threat to all of this is, of course, Klaus Iohannis: a Lutheran, a German and a strong advocate of the European Union. Polls currently have the mayor slightly trailing the PSD chief, whose assault on Iohannis has been so ruthless that even the Romanian Patriarchy has publicly shunned Ponta’s bashing. On November 16th, Romanians will decide whether to follow suit.

Photo of Victor Ponta courtesy of www.romanialibera.ro