The recent history of Zenica illustrates how the transition and economic policies promoted by international organisations have left former industrial centres without hope for a better future, and driven out the people who represented a chance for civic coexistence in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Zenica was developed as an industrial town.

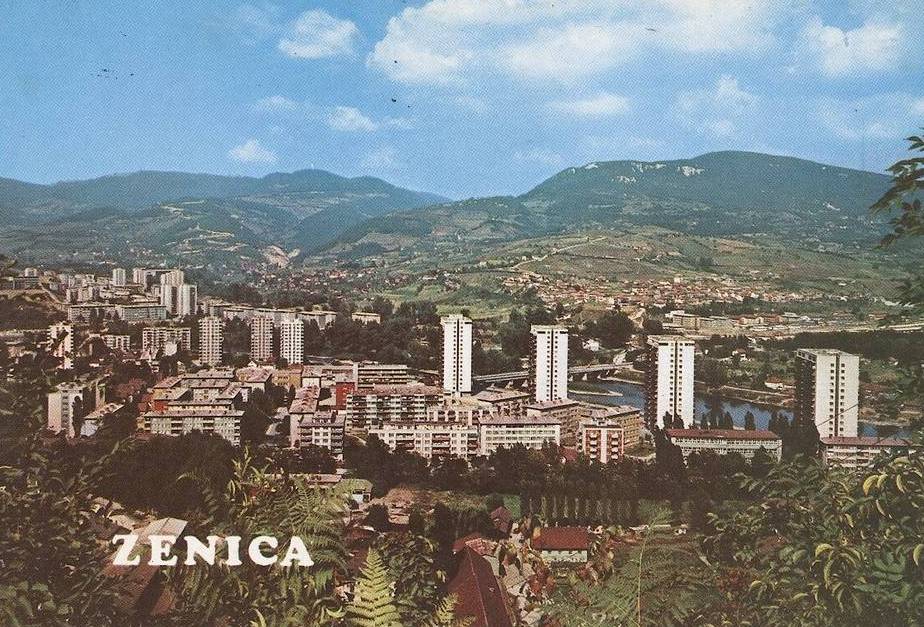

It was nothing more than a village in the central Bosnian countryside, surrounded by hills covered by fruit trees, when the steel plant (Željezara) was opened towards the end of the XIX century. Yet, it was only after the Second World War that the huge investment of the new socialist government in the steel plant transformed Zenica into a proper urban centre. The great demand for workers was met by an influx of thousands of people from the rest of Yugoslavia, for whom the government promised to provide housing in new high-rise complexes. The most impressive of such residential complexes, Lamela, is a 27-storey building reaching almost 100 meters in height and hosting about 250 apartments.

The socialist government also built a library, cinema, university, schools, and other amenities needed to address the needs of the population in the rapidly expanding city. The Željezara built Zenica, and Zenica became known for it. As many citizens will tell you, Zenica’s identity is first and foremost as a working class, industrial town. At its peak, the steel plant employed approximately 20,000 workers in a town of 90,000 people. Like other socialist enterprises, the company had its own doctors, pharmacy, cafés, bakeries, and holiday retreats for its workers.

Today, following the 1990s civil war and the painful privatisation process that followed as part of Bosnia’s ‘transition’ from socialism, the picture is rather different. Only about 2.000 workers work for ArcelorMittal, the multinational company that bought the biggest part of the steel plant, and a few more hundred workers are employed in the part of the Željezara that survived. ArcelorMittal was also at the centre of controversy due to their ownership of areas around the former Omarska camp for the Muslim population during the war, and their refusal to allow family members of the dead to visit the site or erect a memorial. Not only did Zenica lose thousands of jobs in the process, it also lost much of its potential for economic survival during the transition as well as an important piece of its identity. Many of those who worked there left the city, while some of those who stayed live on low pensions or subsistence agriculture.

This raises two questions, the first one of which is related to Zenica’s prospects for economic development. What is the impact of the economic policies promoted by the EU and International Financial Institutions (IFIs) towards Zenica and other Bosnian cities with a similar history of transition? Economic policies became the focus of the EU engagement in BiH following the socioeconomic protests of February 2014 and the floods in May.

The EU-sponsored ‘Compact for Growth and Jobs’, formulated in close cooperation with the IMF and World Bank, suggests a set of reforms which political elites need to undertake in order to make progress on the path of European integration. The Compact, however, merely presents in a new guise a series of economic policies that were already part of the IFIs and EU repertoire. Some of these reforms, such as cutting benefits for some ‘privileged’ categories, such as public employees and veterans, will be very hard to achieve. Most worryingly, however, the Compact does not consider any measures for the recovery of economically depressed areas such as Zenica. It does not address the need for substantial economic investment, which is unlikely to come from the private sector, neither domestic nor foreign, in a country scoring lower than Ukraine and Lebanon on the World Bank’s ‘ease of doing business’ indicator for 2014. For a city like Zenica, reducing taxes on jobs and introducing flexibility in the labour market will not mean much if there are no employers to offer jobs. Reducing public spending and reorganising social transfers does not, in itself, create economic opportunities and is likely to have adverse social effects on weak sectors of the population that international organisations might not anticipate.

The second, related question raised by the collapse of the Željezara is one that is often raised in the former Yugoslav context, namely: where have the workers gone? What happened to them when the steel plant dramatically reduced its number of employees? But also, what has Zenica lost with them? Many people left the city during the war and did not return. Some who stayed in Zenica are lucky enough to receive remittances from relatives who are part of the Bosnian diaspora in Germany, Austria, or the United States. While part of the population has resorted to cultivating the land to support themselves and their families, locals point out that the pollution caused by the steel plant represents a significant obstacle to the development of agriculture in the area.

The consequences of the disappearance of workers from a workers’ city are visible. While they left or retreated to more private lives, people from the surrounding settlements arrived in the city, contributing, many say, to the re-traditionalisation of customs. The generation of those who worked in the steel plant were an emblem of the success of the Yugoslav project: the Željezara was a multi-ethnic and multi-national working place. Social activities revolving around the steel plant further contributed to a shared life experience, and people from the city were used to mixed marriages and a secular lifestyle. Ultimately, work and production offered a way of uniting Yugoslav citizens on a civic basis as opposed to a national one. Today, the disappearance of workers contributes to declining prospects for such civic unity in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The dire social conditions caused by high unemployment also represent an opportunity for nationalist parties to hold on to power, exercised through clientelistic networks, further reducing the possibility for social mobilisation.

Today, as Selvedin Avdić points out in the last pages of his book Moja Fabrika, Zenica is mostly known for its football club, which has some of the most unruly supporters in the country, while the industrial identity of the city is waning. Having spent their lives on the shop floor, many of Zenica’s workers see production as the only way to redeem the city. Unfortunately, the current state of the economic policies proposed for BiH by the international community do not seem to leave much hope for that to happen. Zenica and other struggling industrial towns are paying a hefty price for it.