93 Photos

The grandiose vision of a multi-millionaire porn mogul from Brooklyn, the Haludovo Palace Hotel on the Croatian island of Krk was the most opulent and debauched in the communist world. These days, however, it’s a sprawling ruin in an advanced state of decay, a casualty of “transition”, and a piss-poor privatization process. And Haludovo is just the beginning. Part one of a two-part story on Croatia’s hotel industry nightmare.

When Croatia joined the EU earlier this summer, some people celebrated like it was New Year’s Eve. Others (mostly concentrated in the northern eurozone) were downright macabre about it, writing morbidly catchy headlines like, “Croatia will be a new cemetery” and “Europe’s new threat: Slow decay”.

Unfortunately, the gloomier predictions and death metaphors are fitting in at least one respect. Though the Europhobes may sound as if they’ve done nothing all year but sit in a basement fretting over the inevitably Balkan source of the next European “disaster”, their fears do seem justified if you take a look at the disastrous state of Croatia’s hotel industry. While coastal tourism in the newest EU member state may appear to be humming along just fine, there is trouble in paradise.

Along with a nice stretch of Adriatic shore, the union has inherited the rapidly decomposing remains of Yugoslavia’s abandoned tourism infrastructure. There are literally dozens of ruined and hazardous former hotels, casinos, and sprawling state-owned resorts that are in desperate need of investment (or some other form of intervention), but everyone in charge seems dead set on on doing absolutely nothing.

Part I of our series on Croatia’s beleaguered hotel industry details the rise and fall of the Haludovo resort, one of the most ambitious hotel projects of the 20th century. These days, it’s a deteriorating death trap. When I visited the site a few weeks ago, I ran up the staircase with its missing steps, climbing all the way to the top floor. I was on the hunt for what promised to be the pinnacle of socialist luxury: the master suite, the same room where Saddam Hussein had stayed years ago, possibly with a Penthouse model. So I carefully made my way down the dark, debris-strewn hall. When I entered the deluxe mahogany suite, an enormous bed frame, possibly a California king, dominated the room. All of the windows had been busted out, but this let in some asbestos-free air, and offered a perfect view of the impossibly blue Adriatic. This moment of serenity was broken rather abruptly, however, when I felt a section of floor begin to buckle under my feet.

Sometime during the late 1960s, American multi-millionaire and porno czar Bob Guccione came to the island of Krk in Yugoslavia and had an epiphany. The paterfamilias of Penthouse magazine was wading into the Adriatic Sea when he suddenly felt an earth-shattering revelation coming on. All at once, Guccione realized he’d detected “a real formula in the struggle against the Cold War”.

His formula was this: He would build the Haludovo Palace Hotel and Penthouse Adriatic Club Casino, a sprawling, decadent resort in the small island town of Malinska. It would draw wealthy foreign tourists (and their hard currency) to the unexpected luxury of socialist Yugoslavia. And it would bring Cold War foes together to enjoy leisure activities in the same sensuous, Penthouse-branded paradise.

The King of Porn had found his “Xanadu”, somewhere he could build his own little empire that would bring about world peace through the pursuit of pleasure. The project appealed to Guccione’s vanity and his personal ambitions: There was nothing he craved more in life than to be recognized for something other than porn.

At first, it seemed the timing couldn’t have been better. Yugoslavia abolished the visa requirement for foreign tourists in 1967. Rijeka airport, located just 15 minutes from Malinska on the island of Krk, opened in 1970. There were even rumors that the island airport was actually part of a deal Guccione had made with Tito, a communist dictator and like-minded hedonist who enjoyed women, cigars, and custom limos.

It also seemed like a great time for foreigners to build casinos. According to a Radio Free Europe report from 1973, the Yugoslavs had no idea what to do with them (as one official said of the gambling industry, “we have no expert cadres”), so they went completely untaxed for years. This oversight allowed some foreigners to make a lot of money. While citizens of Yugoslavia could not enter gambling establishments, foreign tourists certainly could, and Croatia generated about 80 percent of the country’s annual tourism revenue.

Still, there were a few minor restrictions placed on casinos or “pavilions for games of chance”, as they were known in Yugoslavia. For example, according to casino director Nino Spinelli, gamblers were never allowed to lose too much money — the upper limit was about $36,000. “The losses in our casinos are never so high as to force anybody to commit suicide,” he explained.

Guccione would later say the flexible business climate appealed to his Sicilian side. As the porn baron told one newspaper, “The workers’ council is a joke. They’ve agreed to everything we want to do. They bent the rules as much as they could to let us in. The Yugoslavs are really ideological soulmates.”

Given the largely permissive attitude of the day, Guccione decided it was a good time to think big. So the pornographer who was never seen without a gold medallion around his neck invested $45 million (about $250 million adjusted) in the project, plus an additional $500,000 for advertising. A state-run company based in Rijeka called Brodokomerc served as the official owner.

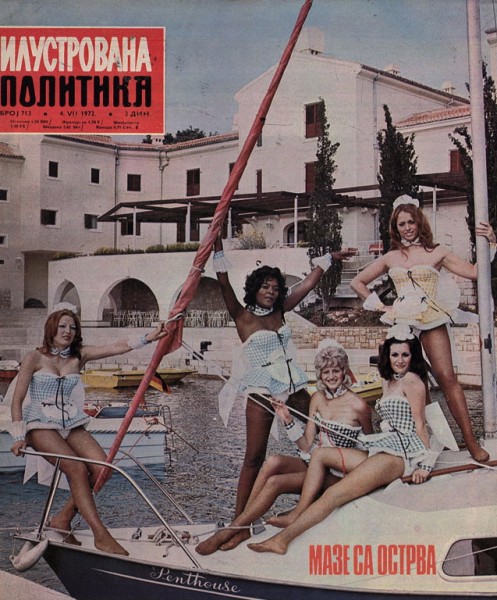

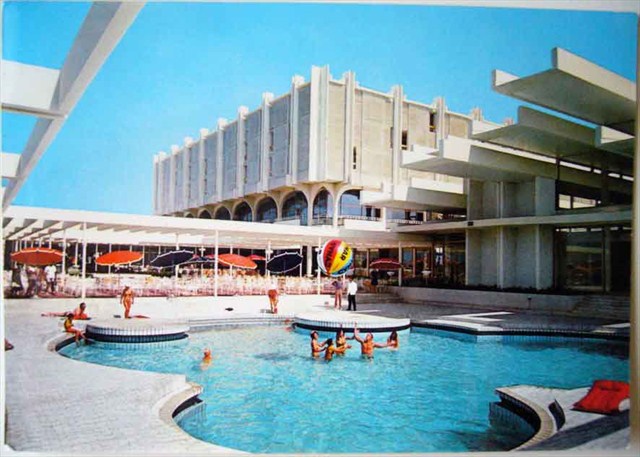

The Haludovo Palace Hotel and Penthouse Adriatic Club Casino opened in 1972, after nearly four years of construction. The final product was opulent and strikingly modernist. In fact, it was probably the most extravagant construction project ever realized in a communist country (excluding anything built around a personality cult). The chief architect was Boris Magas, who designed many important structures in Yugoslavia, including the Museum of Liberation in Sarajevo and Poljud stadium in Split. The garden sculptures were the work of Frano Krsinic, who was already famous for his Nikola Tesla statue in Niagara Falls State Park, New York.

The Haludovo resort had everything a leisure enthusiast could possibly want: plush carpets, glittering chandeliers, poolside cocktail service, a bowling alley, lush hanging gardens, beaches, its own medical center, a fishing village, saunas, a sports bar, hand-sculpted statues, a beauty salon, a masseuse, and an enormous kitchen stocked with lobster, caviar, and champagne. During this early, heady period, it was estimated that hotel guests consumed 100 kg (224 lb) of lobster, 5 kg (11 lb) of caviar, and hundreds of bottles of champagne each day. The hotel had both indoor and outdoor swimming pools, and at one point, there were rumors (still unverified) that one of them was filled entirely with champagne.

Guccione wanted to bring everybody to Yugoslavia. He almost hired a Manhattan plastic surgeon who’d invented a new facelift to work at the hotel’s beauty spa before an assistant found out that the “surgeon” did not have a medical license. However Guccione did succeed in bringing quite a few other Americans to Haludovo to work in the hotel, including a dozen or so young women who worked as hostesses and croupiers. These young ladies were among the resort’s 50 Penthouse “pets”, all dressed in tiny French maid uniforms. They sometimes met Haludovo guests at the airport, and their presence helped make the hotel very popular. But they weren’t just there because they were beautiful (though they were). At the opening of the Haludovo resort, Guccione told a film crew from Belgrade that the semi-nude young women were “the peace forces of the new world”.

Guccione would later elaborate on his world peace project. He said he’d wanted to bring American workers to Yugoslavia so they could labor alongside citizens of a socialist country. As he told Belgrade’s NIN magazine, “In order to defeat ignorance it is necessary to develop communications between people. In this connection tourism is certainly one of the most powerful forms of communication. Through the realization of this project we have the opportunity to start a big process of re-education: We have become partners in removing doubts and ignorance.”

The Krk island resort did succeed in drawing important political figures together from different corners of the globe. Saddam Hussein was one of Haludovo’s more prominent guests, and famously left a $2,000 tip for a particularly pleasing pet (Hussein’s flight back to Baghdad was allegedly delayed because his son forgot a golden pistol beneath a pillow in his suite). In 1974, the mayor of Zagreb hosted a delegation of officials from California at Haludovo to discuss cooperation in the tourism sector. Swedish prime minister Olof Palme, who had adopted a critical, “non-aligned” stance towards the Cold War superpowers, also stayed at the hotel. Of course, Yugoslavia’s red bourgeoisie also gathered at Haludovo to nibble Kladovo black caviar and swill cold gin.

But in the end, Haludovo overspent so much it couldn’t stay afloat. In 1973, just one year after its lavish opening party, the resort went bankrupt. Though it would remain open for two decades, it began its slow, steady decline.

And Guccione’s career never recovered. The porn czar who once had a net worth of $400 million and had lived in the largest apartment in Manhattan died bankrupt and destitute in 2010. Shortly after Guccione’s death, his friend Anthony Haden-Guest wrote, “What was it that doomed Bob Guccione? That jaunt to the isle off the Yugoslav coast? The resort that didn’t happen?”

Go to page 2