Marking the 25th anniversary of the Maksmir riots, when socialist Yugoslavia symbolically fell apart in a football stadium. Dario Brentin on the birth of the ‘Maksmir myth’.

Very few sporting events in Yugoslav history, if any, have attracted as much intensive and continuous inter/national interest as the ‘Maksimir riots’ of May 13th 1990. It was an event, some commentators suggest, of global significance. After all, it is listed by CNN as ‘one of five football games that have changed the world’. It was exactly 25 years ago today that the game between the ‘eternal’ rivals of Yugoslav football, Dinamo Zagreb and Red Star Belgrade, had to be suspended at Maksimir stadium in Zagreb due to violent clashes between opposing sets of fans. More than two decades later, the dominant narrative in post-Yugoslav societies is that the riots represent the symbolic date when the dissolution of Yugoslavia began – ‘the day the war started’.

Of course, the incident did not just occur ‘out of nowhere’, though it did surprise most commentators, scholars and politicians alike. During the late 1980s and especially during the early 1990s, Yugoslav club football rapidly deteriorated into an ideologically and physically contested terrain. Supporters increasingly demonstrated a strong sense of national allegiance and promoted violence against others on an ethnic and national basis. The increased politicization of everyday life ‘from above’ was accompanied by a politicization of sport ‘from below’. In this politically loaded phase, the atmosphere within stadia often emulated political discourse with mobilizing expressions of nationalist sentiment. This manifested itself in a variety of ways: through the appearance of ‘national’ flags, aggressive political chants, various Ustaša and Četnik symbols, iconography and paraphernalia, and the singing of ‘forbidden and nationalistic song’ and the open pronouncement of anti-Yugoslav sentiments or hatred against ‘other’ republics. Though predominantly visible within the relatively small and socially marginalized communities of ‘football fan tribes’, the tense situation in sporting arenas resulted in recurring and brutal violence emblematic of the critical and fragile condition of the Yugoslav state system in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

During this period of political turmoil and general social insecurity, football-related violence arguably peaked on May 13th 1990, when the game between Dinamo Zagreb and Red Star Belgrade was suspended due to violent clashes. Only two weeks after the nationalist and anti-Yugoslav Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) won the first multi-party elections in the socialist republic of Croatia, the tensely awaited match turned violent when the club’s hooligan groups – the Red Star fan group Delije, headed by future Serbian war criminal and paramilitary leader Željko ‘Arkan’ Ražnatović, and the Dinamo fan group, Bad Blue Boys (BBB) – clashed in wild stadium and street fights. As soon as the ‘fan tribes’ entered the stands, they began exchanging verbal political and ethno-religious insults: ‘We are the Četniks, we are the strongest, we are the strongest’ and ‘Serbia to Zagreb’ came from the south stands, where Delije were located. These chants were countered by ‘When you are happy hit a Serb to the ground, when you are happy slaughter him with a knife, when you are happy shout loudly Croatia, independent state’ from the Bad Blue Boys in the north stands. At one point, Delije started tearing down banners and demolishing the stadium, which led to some minor physical confrontations with Dinamo supporters in the south stands. Soon, however, the Bad Blue Boys decided to assist their fellow club supporters, breaking through the fence of the north stands and brawling with a poorly organized and totally outnumbered police force on the pitch. It resulted in the worst riot in Yugoslav sporting history.

Among the assorted chaotic scenes, there is one incident of particular symbolic weight that can be singled out. At one point, Zvonimir Boban, who was Dinamo’s team captain, entered the rioting crowd to help a Dinamo supporter who was being beaten by police. The stadium applauded the act from the stands with shouts of ‘Zvone, Zvone’. Meanwhile, Boban’s ‘mythical’ ‘Kung-Fu kick’ against a Yugoslav police officer strikingly captured the antagonisms of Yugoslavia’s political situation. It made him instantly ‘immortal’ — not only for Dinamo fans, but also for many Croats. At the time, Boban’s attack was perceived as a brave act of resistance against ‘Serbian hegemony’ within Yugoslav institutions. This hegemony was ‘blatantly demonstrated’ by the unwillingness of the police to defend Dinamo supporters; ironically the officer Boban had kicked, Refik Ahmetović, was a Bosnian Muslim from Tuzla. The kick itself, however mythologized its perception in contemporary Croatia it may be, did represent a strong symbolic act at the time, even if the political implications were not intended. Boban ‘dared’ to publically challenge the whole Yugoslav state system, personified in one policeman. Ultimately, this ‘challenge’ would award him a place in the ‘pantheon’ of Croatia’s greatest national heroes.

Back in 1990, interpretations about who was responsible for the escalation of violence were diametrically opposed in Croatia and Serbia. According to the majority of Croatian accounts, the police – widely perceived as a mechanism of Serb domination – acted inadequately, intervening ‘suspiciously’ late, focusing solely on the BBB and openly protecting the Red Star supporters. The Serbian press held a counter-narrative, which saw the events as a meticulously planned incident orchestrated by Croatia’s new government whose officials wanted to exploit the riots politically.

Today, 25 years later, the Maksimir riots are remembered in similarly divergent ways. Research by Ivan Djordjevic has shown that in Serbia, media and popular narratives about the riots are mostly characterized by ‘silence’. Furthermore, there is no mythologization of the riots by Delije. This is quite understandable since they were ultimately the symbolic losers of the riots, particularly if one interprets them as ‘the day the war started’. In addition, Serbian public discourse is still very strongly defined by a lack of consensus in dealing with the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s and the question of Serbian responsibility. With regard to football fan tribes, who were among the first to volunteer for and operate in paramilitary combat, this translates to having to construct a sense of pride for having given their lives in a war in which Serbia ‘officially never took part’.

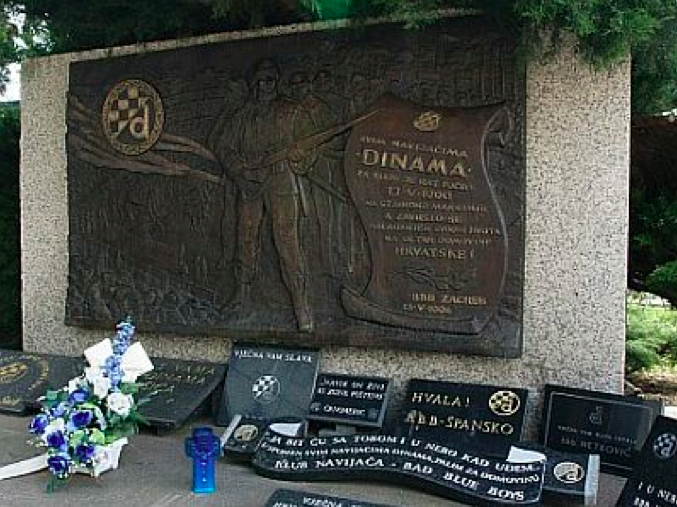

In Croatia, the Maksimir riots must be identified as a contemporary Croatian myth. Just outside of the stadium, the Bad Blue Boys erected a monument to their fallen friends with the inscription: ‘to all Dinamo fans for whom the war started on May 13th 1990 and ended by them laying their lives on the altar of the Croatian homeland’. The myth of Maksimir functions as a founding myth of post-socialist Croatia, which supports the dominant national narrative of Croatia’s formative years; namely the inevitability of the Yugoslav dissolution and the formation of a Croatian nation state as a conditio sine qua non. It was the politicization and subsequent ideological exploitation of the events under the 1990s Tuđman regime that led to their mythologization and established the widespread narrative of the game as a symbolic initiation of the Homeland War. By excluding political alternatives and competing narratives which portrayed the formative years as a contested political struggle rather than a ‘manifestation of people’s will’, a notion of ideological homogeneity of Croatian society was constructed, which functioned as a mechanism to secure legitimacy.

And yet the ‘war’ definitely did not start at Maksimir on May 13th 1990. There is no doubt that sports in late-socialist Yugoslavia can be described as a ‘national motor’ and that the Maksimir riots reflected the political tensions which existed and were developing in the socialist federation at that time. One observation that has been echoed by several critical scholars such as Gal Kirn is that the riots represent an incident in which football became political in a direct way, a social catalyst and condensation of the social complexities that triggered major social change. I would add that the riots themselves should be understood as a ‘condensed symptom’ of an ongoing political radicalization in the Croatian and Serbian republics and a deductive ‘consequence’ of these polarizing policies. Maksimir was the beginning of an accelerated process, in which sports would become a significant nationalizing and homogenizing factor in some of the Yugoslav republics.