23 Photos

Plans to redevelop Sarajevo’s Jajce Barracks, devastated in the Bosnian war, are caught in the legal limbo of restrictions on urban development still enforced by the 1995 Dayton peace agreement.

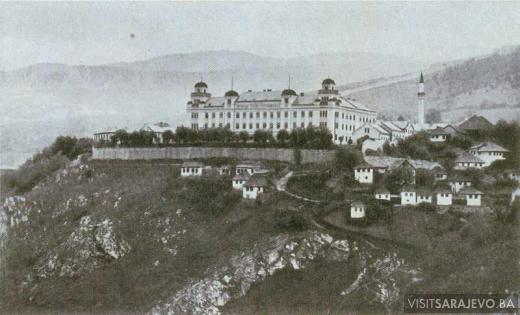

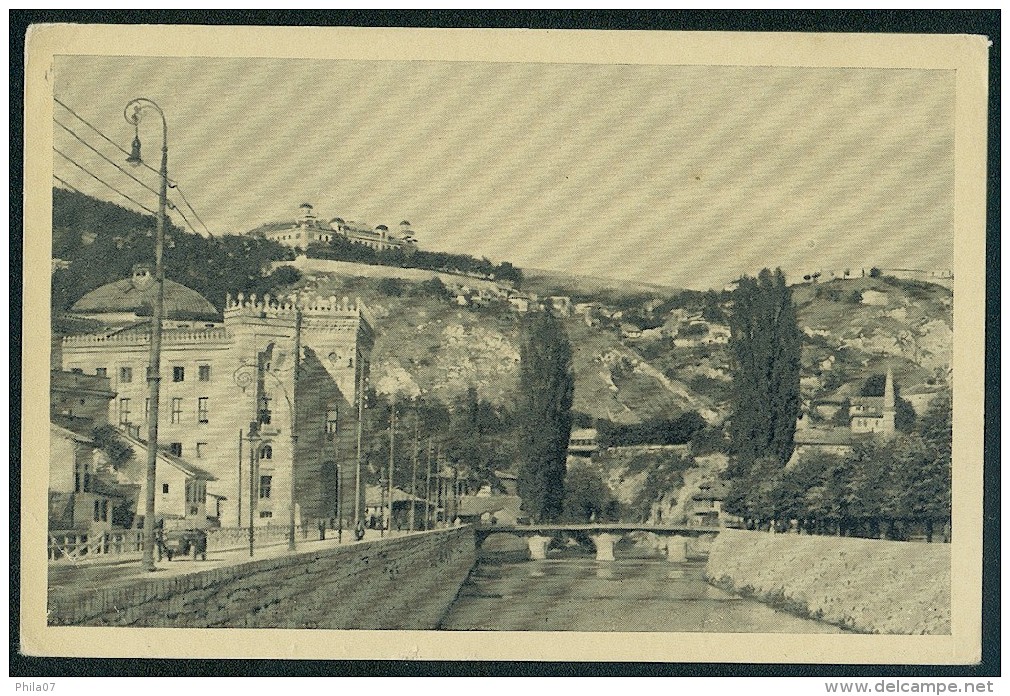

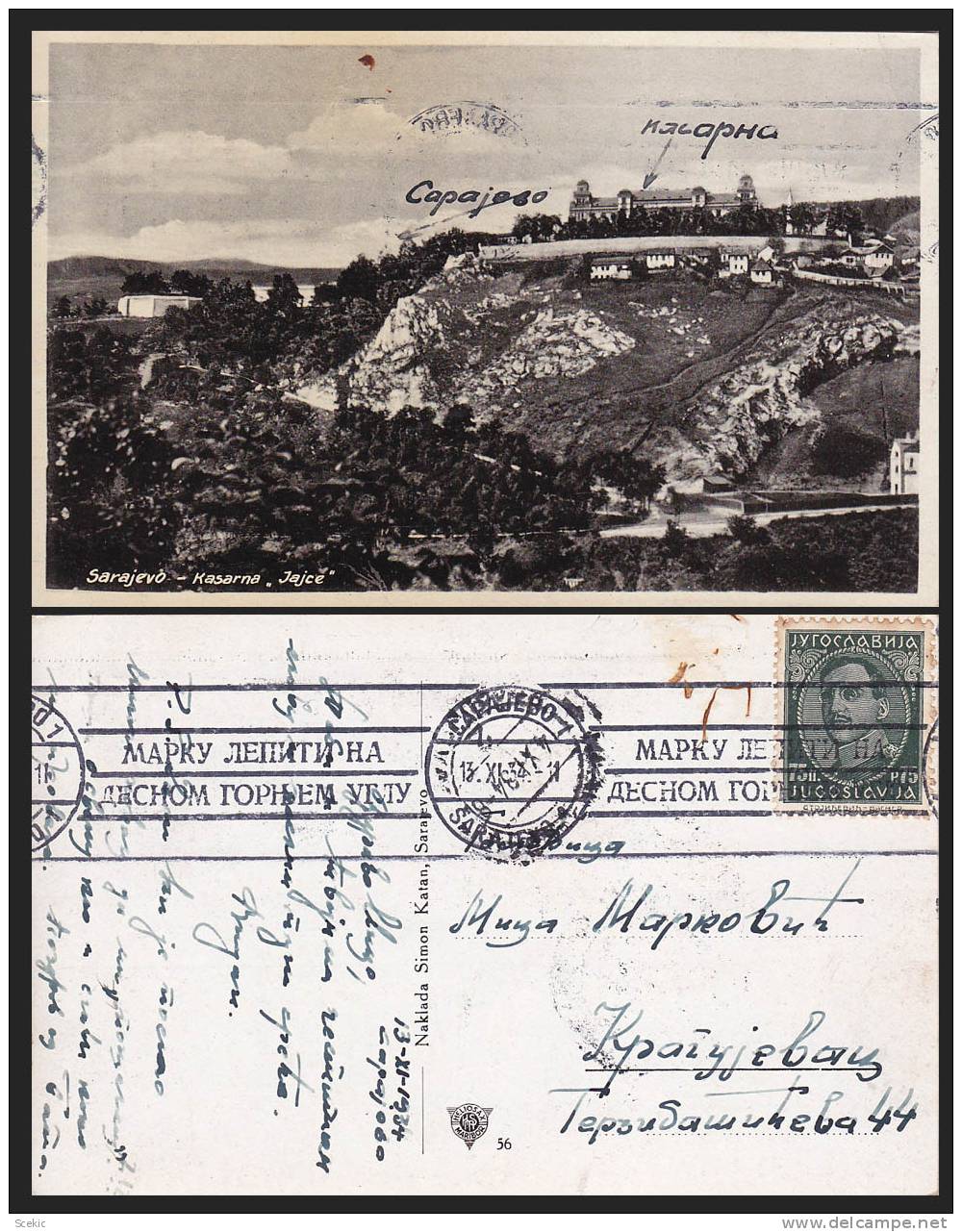

From almost any point along the road that connects the old and new poles of Sarajevo’s historic and commercial centers, the Jajce Barracks can be seen up among the north-eastern hills. From a distance, the national monument’s domed towers and intricate molding are reminders of the city’s fin de siècle boom years under the Austro-Hungarian empire. But as you approach, the grandeur of the relatively well-preserved front façade gives way to the sight of the caved roof and toppled walls, abandoned since they were damaged during the 1992-95 Bosnian War. The vantage point that invested the building with strategic importance when it was built in 1914 now ensures that it’s a conspicuous blot on a skyline that otherwise seems to have recovered well from its wounds. The 17-year restoration of the neo-moorish National Library, which became a symbol of the conflict after 90 percent of its two million volumes were lost to Serb incendiary shells, is approaching completion, and new skyscrapers have sprung up around the business district of Marin Dvor. But the barracks have meanwhile lain empty for almost twenty years, the entire right wing collapsed, the left barely holding. Only from an aerial perspective does the architectural ambition of the original building appear intact, its “E” shape – supposedly designed to honour the Habsburg Prince Eugene of Savoy, who routed the Ottomans from (and destroyed) the city at the Battle of Zenta in 1697 – still discernable.

Walking towards the barracks from Pigeon Square in the center of the Old Town, five minutes are all it takes to forget that we’re in a European capital. The streets quickly steepen, the roads deteriorate, and we realise just how thinly spread the city is, rarely straying far from the Miljacka river. Once we leave the center’s apparently comfortable blend of brazenly tourist-oriented souvenir shops and seemingly authentic local cafes, there is little to distinguish the dense residential sprawl, until the houses open up onto the Islamic Kovaci cemetery, one of the many clearings of pure white column-shaped headstones that punctuate the pace of the skyline in every direction. These resting places’ elevated perspective over the city is a dark reminder of the dominance the Serbs claimed while they besieged Sarajevo for almost four years.

As we approach, the extent of the damage quickly becomes clear. The steps to the door and the courtyard flagstones are uneven, and weeds are growing through the cracks that have formed. Plants have taken hold in the spaces left by broken windows, and have even climbed the main clocktower, slowly advancing on the extremity of the bare flagpole. The peeling magnolia paint has turned a sickly grey, and an ornate border is all that remains of the coat of arms above the main entrance. Inside, the only traces of human activity are those of boredom – on the part of military occupants and civilian intruders alike. In one room, a flecktarn of interlocking grey and black shapes has been painted on a wall, camouflage that no aggressor would ever have seen; just outside, green and blue graffiti blooms along the wall of a corridor otherwise lined only with rubble and glass.

Closed to the public, stray dogs and army soldiers alternately patrol the nearby streets. Though no longer a useable military site, the army will maintain a presence until the building’s ownership is transferred from the Ministry of Defense to the local municipality, who are keen to sell it off for development – most likely under plans proposed by Prince Alwaleed of Saudi Arabia for a 50 million-euro luxury hotel. Forty percent of the national army of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) is involved in similar phantom guard duties, and the ruins of the Jajce Barracks are becoming something of an icon for frustrations over the protracted process of property transfer and the broader bureaucracy of peace, as overseen by the Office of the High Representative (OHR) since the Dayton Agreement of 1995. Among the diplomatic cables that Wikileaks began publishing in 2010 is a dispatch from the American Ambassador, Charles English, who writes that “failure to resolve defense property is one reason that Bosnia’s armed forces do not look or act like a real army”.

The site was exempted in 2012 from a ban on the sale of state-owned land (which comprised 53 percent of the entire country), introduced by the OHR ‘to protect BiH’s assets’ from abuse by the authorities in either of the two entities into which the country was split under the peace agreement. The semi-autonomous entities, the Republika Srpska and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which to some simply represent the rubber-stamped partition of what was once a multi-ethnic republic, have been mutually suspicious of the sincerity of one another’s submissions to the higher single national authority, and as a result slow to act.

As unemployment hangs stubbornly around 44 percent and the dream of EU accession progresses only slowly, much of Bosnia is caught in an economic stalemate. The barracks are an inconveniently visible example in the once-thriving capital, with no progress made despite the promise of decentralised ownership and the presence of interested investors. Meanwhile, the guards outside the gates can only look on as their charge crumbles behind them.

This article was originally published on Failed Architecture. All photos courtesy of Ka Wing Chang unless otherwise noted.