To paint, not the thing, but the effect which it produces. —Stéphane Mallarmé

Travel Guide, curated by Luana Hildebrandt, is a group exhibit at the IOMO gallery that brings together new works by European painters from four different countries. Descriptively, the curatorial address makes explicit reference to the pandemic situation, suggesting that the practice of painting bears on our “collective” situation in some way. The exhibit poses a seemingly simple question: Where are we going? It is the eternal quo vadis? prompt. Curious about the works, I visited the exhibit on a Friday evening, but not without difficulty. The gallery is nested within a cluster of contemporary art galleries, adjacent to a highway of sorts, sprinkled with casinos and cheap hotels. While we were casting about the grounds, we were approached by local security guards who cautioned us that crossing through the blackened fields, which supposedly separated us from the gallery, would not guarantee our safe passage, as it was known to have wild dogs crouching in the thick grasses. Indeed, we had such difficulty, that we had to call the gallery owner, who patiently guided us along the long stretch of road. At last we arrived, quite damp as it was raining with gusto, our feet shamefully trailing mud. The gallery owner greeted us with Balkan warmth, and left us to observe. I am not wedded to the discipline of art history—insofar that I do not have specific knowledge of the art object—nonetheless, I am compelled to write about it, knowing that I lack the satisfaction of an object fully grasped. Instead, I will put forth some theoretical conjectures and discuss the artworks in relation to these jottings. Though each painting deserves recognition and analysis, for our purposes I will discuss three primarily: Alin Bozbiciu’s Blind leading the blind (2021), Adela Janska’s Metamorphosis (2021), and Jiri Marek’s Martyr (2021).

To my mind, looking at paintings or other aesthetic objects is not immediate, such that a painting, or other aesthetic object, forces us to enter into a more perceptive space. Helen Fielding describes the process of looking, in a critical way, as “cultivating perception,” which she locates in a phenomenological register. However one approaches the act of looking, whether one uses the language of the “phenomenon,” percepts and affects, or concepts, what is plain is that one must use one’s own body, and that looking is always mediated by something else: space/time, language, history, and so on. How we post our gaze in relation to the painting is significant, and gives rise to questions regarding position and enunciation: what kind of gaze do I pose and what knowledge am I seeking? Am I seeking a materialist knowledge of the painting, or a conceptual knowledge? Once our eyes adjust to the gallery light, a flood of questions and desires are carried with us, as we move around the room. I want to suggest that how we position our gaze necessarily implicates how we “read” a painting.

In these works, the worlds we encounter are real and imagined, depicting both figurative and abstract forms. The mundane everydayness, whose signification—at first glance—we recognize without much difficulty, is juxtaposed by surreal excursions, peopled by feminine sex-bot esque and alien figures. Even the mundane setting of a picnic scene among friends is ominously laden by the threat of engulfment (L.A.S.T) an allegorical specter suggesting that memory can be snatched away from us. This painting seems to suggest that even at our most mundane—something, which has not yet been named—has been transfigured or destroyed. In The Blind leading the blind we are confronted with heavy brushstrokes that compose the background, protruding and washing over the flesh of the fore-grounded figures. Some figures do cling to our attention, as with the figure to the right, haunting the furthest edges of the painting, whose back is turned to us. The figures are casting about in liminal states, painted in a way that emphasizes the in-between: of movement, dress, and degree of consciousness. The eye is called toward many different points, it follows the figures in their miasmic state, and perhaps they are sleepwalking across the surface of the painting. The central figure who organizes the picture’s space, whose robe is being pulled or tugged off by a fractured arm, demands our attention, without instructing us where to go.

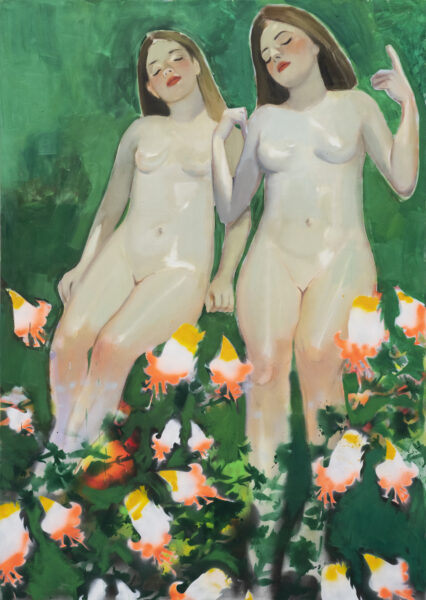

In the first Metamorphosis (there are two paintings that bear the same title), twin female nudes, painted in a glossy, plastic manner, are sprawled in what appears to be grassy field that is laden with stencil-like flowers. The figures reflect the light, producing a centrifugal effect, giving off a synthetic pulse, emanating from, rather than sitting upon or soaking into the plastic flesh. Their insouciance fails to be innocent, for the kitschy atmosphere of the painting and the sex-bot femininity of the figures reads as ironic. By contrast, Martyr employs a darker approach. There is something more primary, geometrical, and forceful about the painting. The white hand, of what could a mannequin, floats in the middle of the painting, dismembered, yet tactile, touching the branch of a black tree, with an owl perched on the right side. The arm is situated above the volcanic figure, which appears to be erupting with substance, looming over it, without suggesting any obvious relation. As viewers, we are left to parse through the density of signification that these paintings present. We become aware, in the double sense of the word: to be aware of something and to be (potentially) weary of what we see. The affective response to looking opens up a space for thought.

If these works operate as a travel guide—if it is possible for them to instruct, direct, or offer a possible response to our disorientation—this task is carried out obliquely. In this case, the guide incites us into stillness. Our position in relation to the works (how we pose our gaze) is directed toward the present, and these works afford us the space to dwell in the present, and this may feel like a form of paralysis. Despite our wishes and desires, art cannot instruct us as to where we are going (at our current juncture, at least). Conversely, works may help us remain “where we are,” in so far that it offers us space to reflect, which includes confronting the weariness of what we become aware of in the process of cultivating our perception, the viscosity of thinking, and the demands that an artwork may impose upon us. If these paintings are instructive, they instruct insofar as they suggest that certainty is not possible; what remains is the present and the not-yet, and this belongs to “us.” Painting often carries a prescient quality to it, offering us visual cues; to this end it is necessary for thinking—to write the present, while standing on a swarm of flies.

The author would like to thank IOMO gallery for their permission to use the artist’s images.

https://iomogallery.com/