Living abroad can introduce a person to a large number of wonderfully confusing new experiences, and for me this past year in Austria has been no exception. Dual control taps, lederhosen, and reliable weather are all features of everyday life that have been grappled with, albeit some more successfully than others. But something slightly more thought-provoking than European plumbing has been the unexpected participation in a community that is so discursively irrelevant where I’m from, that for a long time I wasn’t quite sure how to pronounce it.

Diaspora, as Francesco Ragazzi is at pains to remind us, isn’t a thing; it’s a concept, a discourse, a politicised term that can be used to achieve goals for whoever uses it. But the concept of a British, and certainly an English, diaspora isn’t a discursive tool that gets thrown around very often in the U.K. London got the Olympics and Kate Middleton had a baby, so why would anyone want to leave? The prevalent picture of Brits abroad is either expat pensioners racking up a hefty tan whilst reading exported English tabloids in the Costa del Sol, or short-term pleasure seekers, drunkenly urinating on war memorials in Prague before catching chlamydia in Kavos. Suggesting that there is a large number of Britons who left the isles to permanently seek pastures new both interferes with regular hysteria over immigration (where will we put all the extra Bulgarians who didn’t leap on a cross-channel bus to steal our jobs in January 2014?), and isn’t framed in terms of a relationship with home that is anything more meaningful than occasional cravings for H.P sauce and the ability to watch the Premier league almost anywhere in the world. Emulating domestic culture, the British diaspora is unemotionally reserved about its place in the world; as long as you can still drink Twinings and stream Wimbledon online, there isn’t much more to say.

“But the last time we checked, England isn’t in South-Eastern Europe!”, I hear you cry. With the underwhelming nature of British expatriation in mind, the diaspora experiences which were more of a shock to the system were the ones of my classmates and friends, who are part of a wild phenomenon feared by right-wingers Europe–wide; the Balkan diaspora.

Of course, the practices of my local Balkan diaspora that have been open to participation have largely aligned with another overwhelmingly stereotypical concept, that of student living. In between the essays about Slovenian history and presentations on consociationalism in Bosnia, the opportunity to enjoy home-made pita, smoke “unofficially imported” Drinas and listen to either Yugo rock or Radio Teslić (depending on the quality of the company you keep), is never too far away. And those are just the quiet nights in; for venturing outside there are the monthly Balkan nights at CuntRa, the occasional, very-sweaty Ex-Yu Rock basement parties in a nearby dorm, not to mention the does-what-it-says-on-the-tin Balkan Palace Graz; weekend hosts of esteemed acts like DJ SNS and Olja Bajrami. I missed Elitni Odredi’s visit, because I was too busy drinking rakija and talking about Banja Luka. It’s a hard life, but someone has to do it.

However, beyond the communal cultural practises that are reaffirmed every time someone has a birthday, a far more incomprehensible diaspora activity is a lot more sombre than drunken calls for whacking on a bit of Miroslav Ilić. If you are reading this in the U.K, then it’s entirely possible that the recent devastating flooding in Bosnia, Serbia and Croatia has escaped your attention, and given the minimal media coverage it received there, you would not be to blame. For whatever reason (bad news from the Balkans that isn’t ethnic? Natural disaster not in Africa? British tourists not caught up in catastrophe?), the worst flooding the region has experienced since records began briefly made the headlines before receding faster than the water levels.

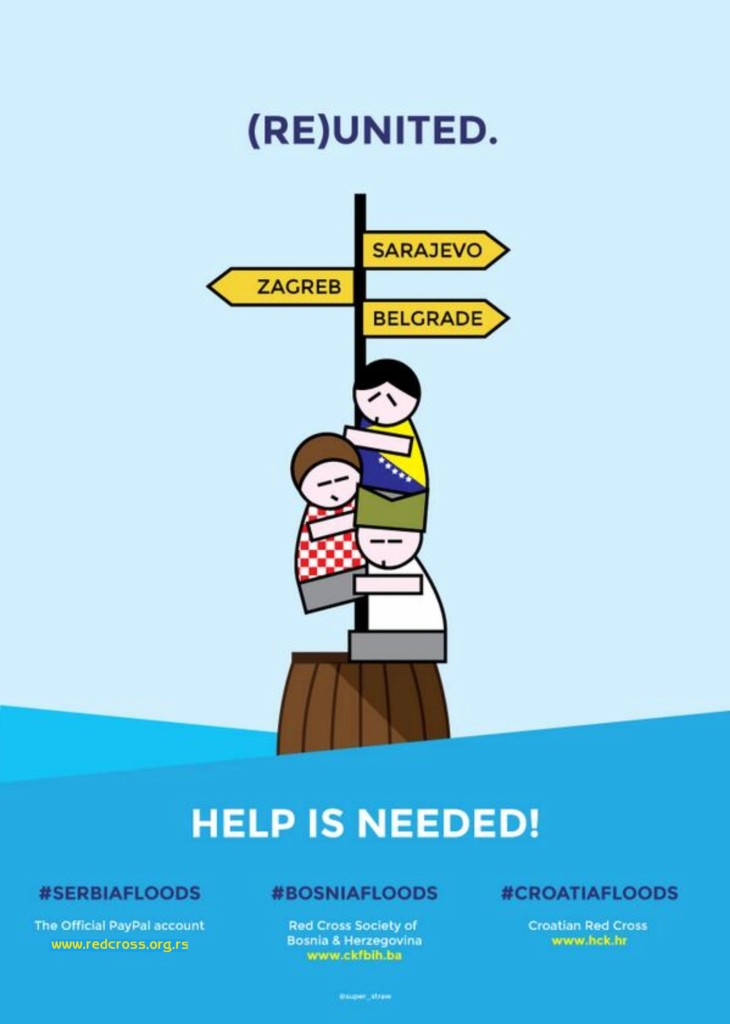

And here is where the diaspora, whoever that includes or whatever that means, comes in. The humanitarian response from outside the borders of the stricken areas was urgent, informal, and collective, with fundraisers left, right and centre, and heart-warming tales of anyone remotely connected doing absolutely everything they could to help the thousands left devastated. Just like a Disasters Emergency Committee appeal, except the appeal was premeditated; people living in Austria aware of family, friends, or just strangers, in Doboj or Obrenovac didn’t have to be cajoled into parting with cash to assist the needy. Before Vučić had pulled his wellies on, they were already mobilized outside Hauptbahnhof collecting donations, co-ordinating personal media appeals across social networking sites, or in some cases, directly delivering supplies from across Western Europe.

Here we find a crucial difference between the Balkan and British diasporas: the condition of your home state. When the south of England flooded extensively earlier this year, the water wreaked havoc, and people’s homes and livelihoods were destroyed. But my concern for those at home did not require any action other than checking in for updates, as apart from complaints that the relief efforts were too slow or concentrated in Conservative constituencies, everyone could be (begrudgingly) confident that the government had a little money available (somewhere) and a rough plan in place to do something about all this extra water. It wasn’t perfect, but at least no landmines were washed away. And no one was relying on remittances from Benidorm to keep a struggling economy from collapsing.

There are many reasons why that hasn’t been the case in the Balkans over the last few months, and these have been covered extensively by Srecko Latal, Srecko Horvat, and Florian Bieber. A lot of unpleasant issues have been unearthed by the currents, and already these are being confronted by the commentators. But alternatively, among the stories of co-operation across so-called ethnic divides, human fortitude, and a common humanity within the stricken borders, a mass-driven and ongoing act of solidarity from outside should also be acknowledged. The diaspora may not be a thing, and may be a loaded, constructed term for politicians to abuse, but it’s also comprised of compassionate individuals who are ensuring right now that buses and planes are being sent to the Balkans full of all that they can offer to a far-away home in serious need. And that certainly deserves a cheers.

This article was originally posted on Remotely Balkan and Laura Wise has generously given us permission to republish it here on Balkanist.