There’s a sense of admiration people across the Balkans have traditionally had for miners, which is probably similar to what Americans must feel for firefighters. What brings these two groups together isn’t just the imagery of their helmets, boots and hard, life-threatening working conditions.

Firefighters in the capitalist West are glorified for saving other people’s property and lives, by risking their own. In communist countries, miners were lionized for putting their lives in danger while building better economic conditions for their country and all of its citizens.

By digging out ore and coal, the key sources of hard industry and energy, they were at the forefront of the nation’s economic development. The citizens of communist countries felt an enormous sense of pride for their production industries, and for the proletariat whose muscle and hammers made dust and smoke rise above the mines and factories, even if this was largely a product of the regimes’ propaganda. Miners held a prominent position among “udarniks”, a term used to describe “super productive” workers across the Soviet-influenced bloc.

Yugoslavia even printed a banknote with one of the most productive miners of all time — Alija Sirotanovic, awarded with the medal of Hero of Socialist Labor, the fourth-highest state decoration. He and his crew once dug out 152 tons of coal in one shift, setting a world record in mining previously held by the USSR’s Aleksey Stakhanov. When Marshal Tito asked him what he wanted as a reward, Sirotanovic reportedly replied he’d like a bigger shovel.

When it became clear that the planned economy was failing and the first political crises arose, miners were among the first to protest and demand a more accountable government and a more just society. In the post-communist period, they’ve mostly gone on strike to protest unsafe working conditions or low wages.

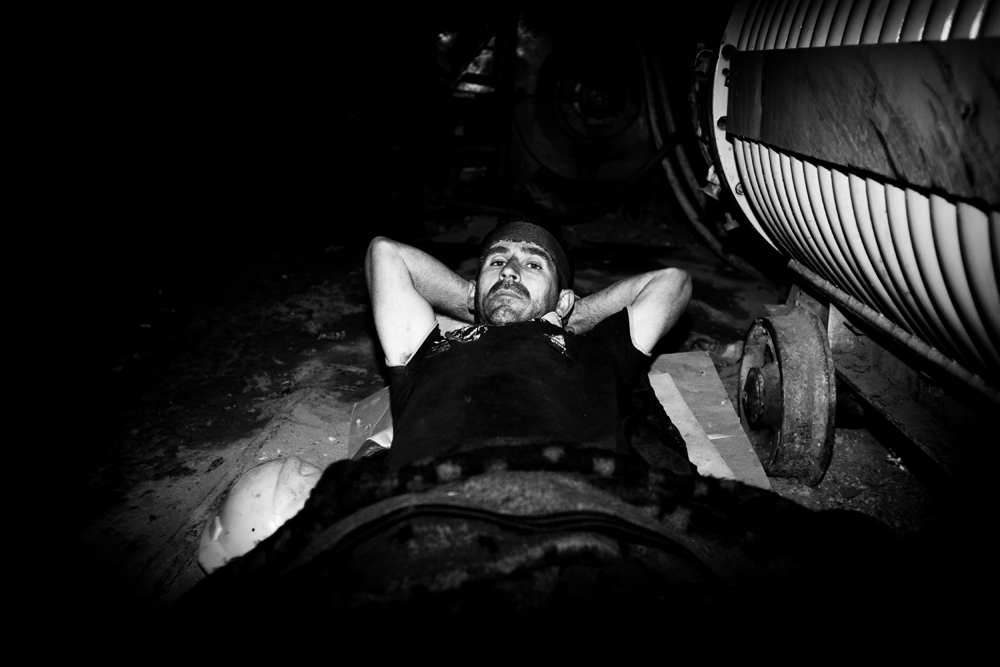

Which brings us to Bulqiza, a chromium mine in eastern Albania. Bulqiza was a source of national pride in the 1980s, as Albania was among the top three chromium producers in the world and the mine was responsible for 80 percent of the country’s overall production. After the fall of communism, Albania’s mining industry collapsed.

Working conditions got worse, and safety precautions were bypassed. There were many serious injuries and even deaths. As the U.S. State Department’s Human Rights Report said of the Bulqiza mine, “Most accidents involved collapses in the mines and were due to a lack of adequate safety measures and procedures…The law does not provide workers the right to remove themselves from hazardous situations without jeopardy to their employment.”

In recent years, Bulqiza miners have gone on strike several times to protest unbearable conditions and the tragic deaths of their co-workers.

In 2005, Prime Minister Sali Berisha promised to review safety measures at Bulqiza after an accident killed five miners. But just two years later, two more miners were killed while working their shift, prompting their colleagues to go on hunger strike. Unfortunately, the protest was overshadowed by the elections and there were no significant improvements.

A 2011 protest in Bulqiza lasted for three months, making it the longest protest since the anti-communist demonstrations in 1990. After five days of demonstrating in Tirana, the miners again went on hunger strike.

After lengthy negotiations between workers and the owners of the mine, it seemed the miners had won. In October 2011, researcher Ermira Danaj said, “This time, the miners have won, but it is one of the very few victories for workers fighting for their rights. The owners of the mine promised to continue investments in the mine, in a transparent manner. They also agreed to improve working conditions, to pay a 13-month wage, to pay the workers for half the period they were on strike, and a wage increase of 20 percent.”

However, only 12 days after this alleged victory, a massive explosion killed another worker and wounded eight others. According to another Human Rights Report, a short time later, yet another worker was killed when a landslide buried him inside the mine. This time, Bulqiza was temporarily closed. Miners never received the wages promised for the months they spent on strike.

Today, the miners’ working conditions aren’t getting any better — a problem which extends to all post-communist countries in the Balkans.

What follows is Ole Elfenkämper’s photo essay of a protest by the Bulqiza miners.

Visit Krautreporter to support and learn more about Ole Elfenkämper’s work, including his current multimedia project about Bosnia.